Presidents: John Adams

Birthplace: Quincy, Massachusetts

Visited in 2008 and 2018

The John Adams birthplace, exterior.

The John Adams birthplace, interior.

The John Quincy Adams birthplace, exterior.

The John Quincy Adams birthplace, interior.

John Adams had his own mini-series, on the same network that brought us "Real Sex," and for that alone we should respect him. John Quincy Adams was featured in that mini-series a little bit, plus he was in that "Amistad" movie, so we should respect him too. And it's one-stop-respectin' when you visit the Adams National Historic Site! In their pursuit of liberty, presidents No. 2 and 6 saw the world. They might be the most well-traveled founding fathers. But you can see all their significant historic sites in about 3 hours.

They're all in Quincy, just south of Boston proper. In the 18th century, Quincy was a relatively sleepy farming community. If you were searching for a good time, you could take the post road to the big city. Otherwise, if you were sticking around, you had to be willing to milk something. Thanks in part to the good work of the Adams family, America has grown and prospered. Quincy has grown with it, and the modern city has engulfed their historic homes. The birth sites for both John Adams and John Qunicy Adams are now on a wedge of grass betweeen two busy roads, and the majority of the farming in Quincy these days probably involves illegal plants and heat lamps.

But the birth homes still have that New England charm. Each structure is what you'd call a "saltbox": big sloped roofs so the snow can slide off, a central chimney, and, presumably, walls made from large bricks of solid salt. That's not practical for wet weather, but New Englanders like it rough. It builds character.

The relatively tiny house where John Adams was born was originally the property of his father, Deacon John. The Deacon was an upstanding member of the Quincy / Braintree community, holding a bunch of public offices and guiding the moral character of the townfolk when he had the chance. His home -- right off the main road -- was used as a public meeting place and makeshift courthouse. So young John Adams was immersed in civic life from the start. Supposedly, the young and studious John Adams was turned off from becoming a minister when he witnessed the trial, in his living room, of a minister who had strayed a bit from the Puritan path. (Probably by buckling his shoes or hat in such a way as to invite the seductions of Lucifer upon his congregation.)

John Adams did the millennial thing and moved in with his parents as a young professional, and so the birth home was also his first law office. It was there that he botched a case about a cow trespassing on someone's property, by goofing up the paperwork. That fateful cow served as a searing reminder of hubris, and so John Adams never lost a case ever gain, ever, or something along those lines. We owe that cow a debt of gratitude.

John's marriage to Abigail merited a change in address, so he took his wife and headed about 70 feet away, to the home on the adjoining lot. That home became his new law office -- the building is a garish orange-yellow, which apparently would have been a great advertisment for his practice. (In the 18th century, only successful people could afford to have terrible taste.) In fact, the home was his base of operations as he worked on his defense of the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre. He won, and that case built Adams' reputation as an extremely annoying, highly principled advocate of the rights of man. There was no looking back.

The "new" home also served as the birthplace and boyhood home of John Quincy. And it was Abigail's base of operations throughout the Revolution, as she was called upon to run the family farm during her husband's long absences. (John and Abigail stayed there until the late 1780s.) The John / Abigail love story has been romanticized a lot over the centuries, and that home might be its main stage.

There's not much to see at the birthplaces, as the homes were extremely modest. But they're run by the National Park Service, so you get a very nice interpretive program. A trolley drops you off, and you have about 30 minutes to pump the rangers for information until the trolley returns to take you to the next stop. Follow the example of John Adams: be ridiculously overprepared, and you'll get the result you're hoping for -- no matter how annoying everyone else in your tour group finds you.

Home: Peacefield, Quincy, Massachusetts

Visited in 2008 and 2018.

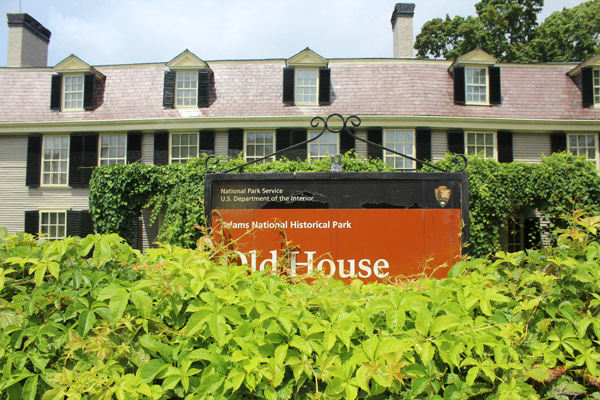

The Old House, a home for four generations of Adamses.

A wide shot of the Old House.

Fine dining the Abigail Adams way.

The entry hall to the Old House.

John Adams' library and place of death. Reading kills, kids.

The master bedroom, for both Adams and JQA.

The marker in a downstairs hallway.

The Stone Library, exterior.

The Stone Library, interior. Awesome!

By 1787, John Adams was a grizzled revolutionary. He had pushed the colonies to rebel, dragged the doubters through the process, and begged for money in the courts of Europe to keep the revolution alive. He set aside some time to write the Massachusetts constitution, and he even agreed to the unpleasant assignment as ambassador to the country he had rebelled against. No one there much liked him, and they didn't really care enough to hide it. In true American fashion, he had EARNED a bigger house.

So he got one. While living in London, Adams acquired a 40-acre spread not far from his home. When he returned to America, he and Abigail realized that their new residence was ... a run-down dump. The structure was beat up and too small for the Adams family. Fortunately -- for John, at least -- he didn't have to live there all that much. His political obligations called him to New York and Philadelphia for long stretches, and he served as the vice president and president of the newly re-constituted United States. Abigail once again took the short straw and oversaw the expansion and pimping out of the new residence. The farm was called Peacefield,"and the building was simply "The Old House."

What's standing today is fascinating. Peacefield stayed with the Adams family for four generations, and then it was handed over to the government. And none of those generations sucked. John Adams made The Old House the center of his retirement; John Quincy called it his Boston-area summer home for his presidency and then a distinguished 18-year tenure in the House; Charles Francis Adams was a leading public intellectual and ambassodor to the U.K.; and Brooks Adams was a distinguished historian. (Henry Adams, the brother of Brooks, also spent a lot of time at the propery, when he wasn't in DC drinking cocktails with half the executive branch every night.) The property was given to the government on the condition that it not be changed, and so you aren't seeing the home of any one Adams. You're seeing a conglomeration that serves as a monument to all of them. (And, of course, their highly capable and intriguing spouses.)

There is some seriously cool stuff. John's library is a beautiful room, complete with the ugly wingback chair where he sat on his last day on Earth -- July 4, 1826, when he allegedly / erroneously croaked "Thomas Jefferson survives." The dining rooms and parlor, where the Adamses entertained thousands of guests over the years, are decked out to Abigail's specs. An upstairs hallway holds an unbelievably rare print of the Declaration of Independence presented to JQA, now hanging on the wall like the Led Zeppelin posters in your dorm room. Especially impressive is the Stone Library, built in 1870 to house the family's papers; it's a separate structure with something like 12,000 books and working desks of both presidents. It looks like the kind of room they could use in "National Treasure 3." Charles Francis and Henry used it as their office when working on hugely momentous histories of the United States.

Even with the many expansions over the years, the Old House is still ... well, an old house. Some of the hallways are a little tight, and given the priceless nature of many furnishings, you don't have the ability to roam freely. They keep the tour groups realtively small and on a crowded day you might get pushed through faster than you'd like. But it's run by the Park Service, so you won't be disappointed by the quality of the guides.

And there really is no other presidential home quite like it. There are other multi-generational sites that you can visit, but they don't strive to capture the breadth of history that the Adams site does. Go see it.

Grave: United First Parish Church, Quincy, Massachusetts

Visited in 2008 and 2018.

The approach to the "Church of the Presidents."

John Quincy's pew.

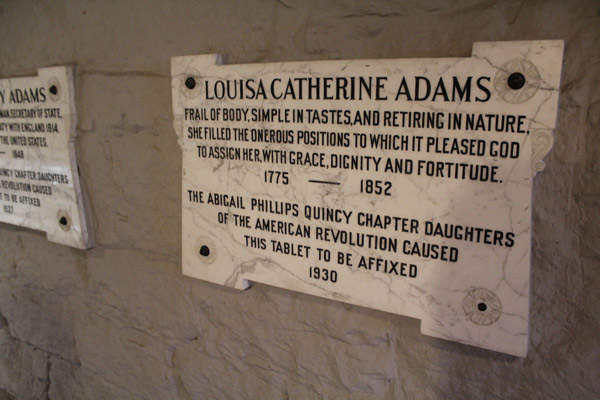

A strange marker for a curious lady.

John Quincy's sarcophagus, in the crypt.

John's sarcophagus, in the crypt

Public service was a family affair for the Adamses. And if something works for you in life, why not keep it going in the afterlife?

At an early age, John Adams abandoned his plans (or his father's plans) of becoming a minister. But he didn't abandon religion. John was a member of the United First Parish Church (est. 1639!), and when the congregation wanted a new building, he answered the call. He was old, widowed and semi-retired, but he had the means to help. In 1822, Adams donated some of his land to the town, including a quarry; the income and materials from that property made construction of the "Old Stone Temple" possible. When the church was completed in 1828, it must have been a stunning sight: the building would have been towering over the local farms.

John Adams, however, never saw the finished product. He died in 1826, at the stunning age of 90. His son was busy serving as president at the time, and when the news reached Washington, John Quincy headed north. By the time he reached his hometown, it was too late. His dad was already laid to rest.

But he didn't have to stay there! JQA was also active in the congregation, and he requested that the church make space in the basement for his parents. The congregation gladly obliged, and they even expanded the space to fit JQA (died 1848) and his wife (1852) after they kicked their breathing habits. JQA composed the text of the marble tablet honoring his father, which is set in the wall near the pulpit. Everyone worshipping can see it, plain as day.

United First Parish takes pride in being the "Church of the Presidents"; it's the only place in America where two presidents are interred side-by-side. (Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond comes close, but the odd couple of James Monroe and John Tyler aren't quite next-door neighbors.) When you visit, they'll run you through the history of the building, and if you want you can sit in the pew that John Quincy Adams used to rent, while you're listening. Afterwards they'll take you down to the vault, where you get as close as you possibly can get to a dead president -- no bars, no red velvet ropes, no burly guys in leather vests telling you that you aren't on the list. Awesome.

The inside of the vault has the four sarcophagi, plain white walls, and barely any space to move around. You can touch the stone and no one yells at you. The Adamses -- some of the most prickly, difficult public figures of their day -- have become the most accessible, democratic presidents in death. Cool.