Presidents: Ulysses S. Grant

Birthplace and Boyhood Home, Southwest Ohio

Visited in 2013.

The building that makes Point Pleasant so darn pleasant.

Looking up the road at ... well, most of Point Pleasant.

Point Pleasant: Inside Grant's birthplace, where the magic happened.

The thriving commercial sector of Point Pleasant.

Point Pleasant: They squeezed in an extra memorial to Grant, just in case.

Georgetown: Grant's boyhood home: A house that leather built!

Georgetown: Jesse Grant was apparent pretty good at tanning things.

Georgetown: Seriously, how much money do tanners make? I need to change careers.

Georgetown: One of the old schoolhouses where Grant got his learn on.

Georgetown: And here's the tourable schoolhouse, a few blocks away.

Georgetown: Where Grant learned abour Reading, Writing, and Rebellion Crushing.

Georgetown: Grant's old desk, allegedly. He drooled on it many times.

If you follow the Ohio River east from Cincinnati, before too long you get to Point Pleasant. The town has about 50 people today, which means it has exploded in since 1822, when it consisted of three houses. When Hiram Ulysses Grant was born, it created a statistically significant spike in the population. The town council seriously thought about putting in a stop light.

Leather goods are the jumping off point for many great adventures, and the story of U.S. Grant is no different. His father, Jesse, worked in the Point Pleasant tannery and rented a frame cottage from his boss. About a year after his first son was born, Jesse moved the family to Georgetown, Ohio, where there were exciting new opportunities in the leather business. It had just been named the county seat, they had just opened an S and M club, and no one made a finer gimp costume than Jesse Grant.

Allegedly. Take your historical anecdotes with a grain of salt.

Fortunately for Point Pleasant, Grant's brief stay was enough to keep the town on the map until the end of time, or at least until the Chinese invade and start redrawing our maps. The birth house has actually gotten around: back in the day, after Grant had become a national hero, it was shuttled around to different fairs. By 1896 it was contained in a permanent structure on the state fairgrounds in Columbus. They finally brought the home back home in 1936 and installed it on the original foundation. It has been there ever since.

It's actually a little larger than when the Grants lived there, meaning it has three rooms now instead of one. The second room is where an old lady sits and hands out pamphlets. The third one has a museum case with, among other things, old buttons and a locket with some of Grant's hair. There's also a caretaker's cottage next door, which is inhabited by the old lady (as of 2013). She was very chatty and pleasant, and when she dies, they are going to have a very hard time finding someone willing to live in Point Pleasant year round and talk to weirdos about history.

It's a nice drive through farm country from Point Pleasant to Georgetown. You can do it in about 50 minutes, which means it would have taken eight months in 1823. When the Grants got to Georgetown, it was small but growing. When I got there, the Grant Boyhood Home was locked and the alarm system was blaring. This gave me the opportunity to wander the streets of Georgetown in a perplexed daze for a few minutes, much like the teenaged Grant probably did.

After about 15 minutes, my guide to the magical world of Grant showed up and unlocked the doors. Apparently, he had to drop his mom off at another nearby historic site, and on top of that it's not all that common for people to show up at the boyhood home exactly at opening time. Go figure.

Judging by the house, Jesse Grant must have been pretty good at tanning things. The Georgetown house started small, but if you count the basement, the finished version is a three-story brick structure with some fairly nice entertaining spaces. I don't know what qualified as upper-middle class in 1830s middle-of-nowhere Ohio, but that was probably it.

Hiram lived there through his mid-teens. According to the legends, he wasn't all that good at school, but he was some kind of a horse whisperer who was insanely good with animals. So think of him as the guy in your high school with a manual I-Roc convertible.

There's also the legend about Grant's start in the military. Then as now, it wasn't the easiest thing in the world to get into West Point. You needed a recommendation from your congressman, and there were only so many slots to go around. One of Grant's neighbors (about three doors down on the other side of the street) got a commission, but flunked out. Hiram was a good candidate to replace him, but Jesse -- who was politically opinionated -- was in some kind of pissing contest with Rep. Thomas L. Hamer. For the good of his son, Jesse asked the congressman for help, and Hamer was cool enough to let bygones be bygones. If Hamer were a douche, slavery would still be legal in the South. Clearly.

Georgetown knows something about catering to the discriminating history tourist, so they also maintain one of the old schoolhouses attended by Grant. There's not too much of interest other than a bench Grant used to use, but the docent was the aforementioned mother of the guy from the boyhood home, and she is happy to talk about his personal life once you've exhausted all the learning opportunities. Apparently she's never getting grandkids.

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site and other Missouri sites

Visited in 2011.

White Haven: The home of Colonel Frederick Dent, father-in-law to the stars.

White Haven: Grant eventually took control of his FIL's property, 'cuz he was good at sieges.

White Haven: Another exterior view. Trust me, there's nothing to see inside.

White Haven: One of the outbuildings at the farm.

Hardscrabble: The house that Grant built, now owned by Budweiser.

Jefferson Barracks: A peek at the park now on the barracks grounds.

Jefferson Barracks: Inside the barracks museum, a converted powder house.

In September 1843, Ulysses Grant reported to Jefferson Barracks, right outside St. Louis. He had graduated from West Point in the middle of his class, he was stationed in the middle of the country, and he was about to blaze a trail to ... well, a middle-of-the-road existence.

Actually, a lot of journeys started at Jefferson Barracks. It was one of the military's most important training and mustering sites from the early 19th century up to 1946 -- Robert E. Lee once commanded the post, Zachary Taylor did a few stints there, and my grandfather did his basic training there in WWII. Today, it has been divided up into a National Guard base, a veterans cemetery, some private housing developments and open fields. A few old powder houses have been converted to museums staffed by very courteous senior citizens. There was a cross-country meet going on when I came to visit, and I think generations of soldiers would be thrilled to know that high school guys in short shorts were cavorting over the same parade grounds where they once froze their nuts off.

For it gets cold on the Mississippi River. My grandfather had stories about overcoats getting so frozen they stood up on their own. Fortunately, Grant's West Point roommate was also at Jefferson Barracks, and that roommate happened to be from the St. Louis area. So whenever Grant needed to escape the bitter conditions at the barracks, there was always the prosect of a home-cooked meal, just a muddy horse ride away.

The home in question was White Haven, the property of Colonel Frederick Dent. The Colonel made his money in fur trading, and that's not a euphemism. That's how people made money in Missouri back then. The house is a glorified log cabin; the main building is mostly vertical timbers that have been plastered over and painted.

As for Fred, he's a glorified Tennessee Williams character -- a domineering, patriarchal plantation owner who wasn't actually a colonel, but insisted on the title. He was a racist and a slave owner, and he liked to be the big shot. He had so many visitors, he painted his front door orange to make it easier for guests to find him from the main road. As the slavery issue started to divide the nation, his home was becoming an island of southern sentiment in a mostly anti-slavery town.

And of course, he had a hot daughter. Well, hot by 19th century standards. At least to Grant.

When presented with a plantation owner's daughter, you pretty much have to hit on her, so Grant obliged. According to the great park ranger who gave me the tour, Julia Dent wasn't exactly receptive. Grant went with the "Steve Urkel" approach (the ranger's words) and wore her down. It didn't sound particularly hot and heavy. The courtship featured horse rides, reading books aloud to each other, and the Colonel chaperoning every meeting for a year. Then, to play hard to get, Grant left to fight in the Mexican-American War.

There's nothing like being shot at by Mexicans to galvanize a love affair, and they were married when he came back. The Colonel thought Grant was a shiftless loser and didn't particularly like him. He decided that the only proper thing was for Grant to move into White Haven, where he could be brainwashed into becoming a Southerner. Grant, realizing the tacit contract when you marry money, obliged. He got a nice chunk of land for his trouble, and after a time he also got a slave from his father-in-law.

To be fair, Grant made some effort to be his own man. When life gives you slaves, make lemonade, right? Grant used his new parcel of land to build the stunning structure known as Hardscrabble.

Unfortunately, it was the bad kind of stunning. Grant built the slovenly cabin with the help of his slave, William Jones, who was freed in 1859. Grant and Julia lived in that craphole for about four months. Then Julia's mother died, and Julia insisted that they move back into White Haven with her dad. Hardscrabble is actually not in its original location; it was moved around a bit and used as a coffee shop in the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. The Anheuser-Busch family bought Grant's old farm as their country estate, and they eventually moved the cabin to a new spot on the property. The estate (right next door to the National Park site that includes White Haven) is now operated as "Grant's Farm," which combines a child-friendly zoo and safari park with an adult-friendly beer garden. For just $11, you can ride on a tram past Hardscrabble at 5 mph and never get within 50 feet of the building. But then you get to pet a goat, so ... I guess that makes it worth it?

But back to White Haven. A funny thing happened in the 1850s: Grant ended up taking over the family. The plantation wasn't exactly lucrative, and as anti-slavery sentiment started to spread, the Colonel found himself a social pariah. The Colonel kept reducing his slave holdings and renting out parcels of his land. Grant himself was struggling to make ends meet, but he ended up slowly acquiring more of the property from his father-in-law. At the start of the war, the Colonel urged Grant to get on board with the Confederacy, but Grant (obviously) declined. The Colonel eventually came to live with Ulysses and Julia in the White House, which had to be the biggest plate of crow any parent ever swallowed.

The X factor in all this is Julia. According to my guide, she was living in the clouds. She enjoyed the perks of plantation living, never really gave much thought to the morality of slavery and focused on her perfect devotion to her father, husband and children. (Three of Grant's four kids were born at White Haven). They have a pretty nice museum in the old barn, detailing a marriage that included some long separations and sincere lovin'. Grant married a flake, but she was a flake with a good heart.

The house today is empty. The Grants rented it out when they left town for military and political pursuits, and when they did so they decided to store all the furniture in the nearby home of a relative. That home mysteriously burned to the ground in the middle of the day -- it might have been arson by abolitionists who were angry at the Colonel -- taking all the original furnishings with it. And the Grants never has a reason to refill the home, as they didn't retire to St. Louis. Grant eventually had to sell his wife's ancestral home to cover family debts. So I guess he couldn't save EVERYTHING.

Ulysses S. Grant Home, Galena, Illinois

Visited in 2014.

Heading up the hill toward Grant's official residence from his presidential years.

The parlor, where men could casually ingest both alcohol and dangerous amounts of lead.

Grant's study, which is a veritable study in studies.

The Grants were apparently expecting me to stay for dinner.

Julia Grant, the most beautiful person to ever marry Ulysses Grant.

Photo evidence that I was in Galena that day, in case the courts ever ask.

I'm pretty sure this High Street home was Grant's original Galena pad.

Strolling through Galena's historic district.

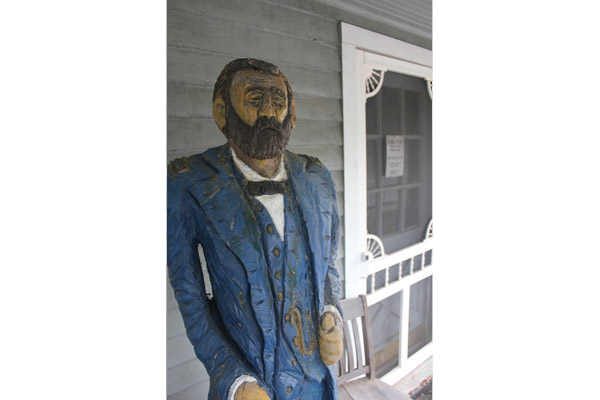

Yes, it's a cigar-store Grant. Miracles do happen.

When U.S. Grant moved to Galena, Ill., in 1860, he had not yet actualized his potential. He was not yet the very best Ulysses Grant that he could be.

Basically, he sucked.

Grant had faded out of the military. He married the daughter of a Missouri plantation owner, but his father-in-law wasn't one of those cool plantation owners from the movies who two-fisted mint juleps and could shower a deadbeat son-in-law with riches. Instead, Grant scraped by as a mediocre farmer and failed businessman in the St. Louis area.

His own dad came to the grudging rescue. Jesse Grant was a tanner, and back then the leather goods industry was for more than bikers and sadomasochists. One of his sons was operating a leather shop in Galena, and at the time Galena was a fairly big deal. It's not far removed from the Mississippi River, and it was home to delightful lead mines that sustained the economy (at least until prudes started to sour on lead's mildly poisonous qualities). Farmers from northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin might come to Galena to drop off crops to ship downriver, and while they were there, they could stop in to the leather shop to pick out a saddle for their horse and a ball gag for the missus. Grant's brother was operating a fundamentally sound business.

However, that brother had tuberculosis, and when you're coughing up blood on a regular basis it's nice to have a little help around the store. Grant took his wife, Julia, and their four children to Galena. They rented a modest home on High Street, on a crest overlooking the Galena River. Grant worked at the store, traveled around as a sales rep and accepted the fact that his soul had been crushed. In an independent film, this was the point where he would either start an affair or take swing dancing lessons in secret.

Fortunately for Grant, fate wanted him to star in a big-budget action flick. When the Civil War started and troops were needed, Grant made full use of his military credentials. He led a bunch of cannon-fodder volunteers to Springfield, and that got him back in the game. He eventually snagged a commission in the Union Army, and the rest is history.

Grant could have washed his hands of Galena, and after that much exposure to lead, washing your hands is sound medical advice. But a group of 13 local Republicans and business leaders figured out that once Grant won the Civil War, he might be a tourism draw. They got together in mid-1865 and bought Grant a new home on the other side of the river, with an even better view. (The truly amazing thing about fame is that once you're capable of buying anything you want on your own, people just give it to you for free.) They gave Grant the house when he came through town on a post-Civil-War victory lap, and it became his official residence for the next 15 years or so. He never really lived there for the long haul -- he was in Washington running the Army, then serving as president for eight years. But the house wasn't rented. A caretaker had it ready to go any time Grant stopped in, and there were rooms for all his kids. Grant voted in Galena, and during his political campaigns he stayed in town.

So there's actually something worth seeing. I came into Galena from the north, crossing the Mississippi at Dubuque and following the river south through ridiculously beautiful countryside. I parked the car in front of Elihu Washburne's house -- the congressman was one of the 13 homebuyers, and for a few weeks he was Grant's secretary of State. Walking down to the river, I got a glimpse of Galena's historic district, which is quaint as hell. And then I walked up the steep hill to Grant's fancy home, to see exactly what you get for saving the nation.

It's not bad at all. I had a nice guide named Vernetta, who walked me through the parlor and the study while sharing most of the information in the paragraphs above. They'll let you peek into the bedrooms, and they encourage you to admire the fine woodwork and wallpapering throughout the building. It's not opulent -- that was never Grant's style -- but it is respectably pleasant. The only ugly thing about the site is a statue of Julia on the front lawn. Speaking strictly as an impartial historical observer, she was a hag. And from what I've read, she wasn't all that bright. There may be a reason her husband was willing to stare death in the face repeatedly.

As of 2014, they were trying to build out the Grant site into a historical district, because the lead trade isn't coming back to bolster the local economy anytime soon. (Fun story: In the Grant house, they have samples of special Galena-produced pottery, which had an iridescent glaze. It's a big collector's item because they stopped using the glaze once they figured out that everyone drinking from the bowls and jugs was getting lead poisoning.) There is a historical general store next door, and a block up the street I spotted an old building with a statue on the porch. It appeared to be a "cigar store" Grant. Considering Grant died of cancer from smoking too many cigars, this is one of the greatest things I've ever seen.

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, Virginia

Visited in 2015.

McLean House, where it's always quitting time.

This tree isn't important but OOOOH it looks good in fog.

Confederate re-enacters on the march to defeat.

Grant rolls up for his meeting with Lee.

Pretty sure that's the actual court house in the background.

The Civil War featured lots of balls-to-the-wall action, but its ending was anti-climactic. It would have been cool if U.S. Grant had punched out Robert E. Lee in a driving thunderstorm on top of a cathedral, seconds before Lee could activate his nefarious Demancipation Device. Instead, they just met in an unimpressive building and talked for a bit. Sigh.

My point: Appomattox Court House is a well-presented historic site, but most people will find it boring. There are a few historic buildings that house decent exhibitions. They are sitting in the pleasant Virginia countryside. There are "living history" elements as well. They tell you about the war, and about life in a central Virginia town in the 19th century. It's the kind of site that's tailor-made for school trips where all the kids hate it, pay no attention and generally disrespect the memory of everyone who died in the war.

So pick your spot! I visited on April 9, 2015, the sesquicentennial of Lee's surrender to Grant. All the Civil War nerds showed up in costume, there was a non-stop schedule of speeches, performances and re-enactments, and they had a better-than-usual assortment of awful fried food vendors on the premises. History is better with funnel cake.

The focal point of the visit has to be the McLean House, where Lee and Grant had the surrender meeting. It had an unusual post-war history; investors at one point planned to dismantle it and ship it to various fairs and exhibitions. They got as far as the dismantling before the plan fell through, and for about 50 years the "house" was a rotting pile of scrapwood. The Park Service acquired the property in the 1940s, and the reconstructed house was opened to visitors in 1949. Back in April 1865, Lee's guys picked the house as the location for the meeting. Essentially, one of Lee's aides rode through town, spotted Wilmer McLean, asked him "where can we do this thing," and eventually settled on McLean's home.

As for the meeting, Grant himself can tell you. From his autobiography:

When I had left camp that morning I had not expected so soon the result that was then taking place, and consequently was in rough garb. I was without a sword, as I usually was when on horseback on the field, and wore a soldier's blouse for a coat, with the shoulder straps of my rank to indicate to the army who I was. When I went into the house I found General Lee. We greeted each other, and after shaking hands took our seats. I had my staff with me, a good portion of whom were in the room during the whole of the interview.

What General Lee's feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassable face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.

General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value, very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia; at all events, it was an entirely different sword from the one that would ordinarily be worn in the field. In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But this was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.

We soon fell into a conversation about old army times. He remarked that he remembered me very well in the old army; and I told him that as a matter of course I remembered him perfectly, but from the difference in our rank and years (there being about sixteen years difference in our ages), I had thought it very likely that I had not attracted his attention sufficiently to be remembered by him after such a long interval. Our conversation grew so pleasant that I almost forgot the object of our meeting. After the conversation had run on in this style for some time, General Lee called my attention to the object of our meeting, and said that he had asked for this interview for the purpose of getting from me the terms I proposed to give his army. I said that I meant merely that his army should lay down their arms, not to take them up again during the continuance of the war unless duly and properly exchanged. He said that he had so understood my letter.

And so on. I got to see a re-enactment of Grant riding up to the house, and then Lee riding off after to address his troops. It was all very impressive, and I was there on the one day a year where that kind of commitment to re-enacting can be considered remotely cool. Next time they have any celebration with "centennial" in the title, you should totally check it out.

U.S. Grant Cottage State Historic Site, Wilton, New York

Visited in 2017.

Grant Cottage, which was actually Drexel Cottage.

A monument to ... uh, Grant enjoying the view of the Hudson Valley.

On a clear day you can see Vermont. Now that's a marketing slogan.

A closer view of the death site of famed author U.S. Grant.

Grant's unconventional, cancer-inspired sleeping arrangement.

Funeral decorations that are more than a century old. Yowza.

Ulysses Grant knew something about sieges, and in late 1884 he realized he was on the losing end of one. He had noticed a persistent sore throat, exacerbated when he ate peaches. Like any self-respecting man's man, he put off seeing the doctor for a few months. But when he finally had it checked out, doctors realized it was throat cancer. Smoking kills, kids.

His decline was rapid. The cancer made it difficult to eat, breathe, sleep and talk. News of his diagnosis reached the press -- a article on his impending death was published in the New York Times in 1885 -- but the general otherwise dropped out of public life. But hey, at least he could die peacefully, secure in the knowledge of a job well done. Right?

Well, no. Grant's life had an odd trajectory. He stumbled through the first stage of adulthood, squandering a promising start in the Army and becoming a serial failure with every other profession he tried. The Civil War was a huge break, as Grant found one thing that he did really well -- wars of attrition -- and was able to follow his bliss. He became the savior of the Union.

And then he went back to failure, only now it was on the national stage. Historians keep re-evaluating Grant's presidency and improving their estimation of his time in the White House. But by most accounts he was not a particularly accomplished executive. He surrounded himself with a lot of scumbags, who traded on his name and power for some very sketchy enterprises. By the end of his second term the bloom was off the rose. The pattern repeated in the private sector, as Grant was wiped out by bad business deals and was scammed out a small fortune by one of his son's associates. By the time of his cancer diagnosis, Grant was living off the charity of the Vanderbilts, who assumed the title to his New York City home and allowed him to stay there rent free. He was selling Civil War mementos to pay his debts. In the 19th century, they didn't have those services where you could pay B-list celebs to send you birthday greetings recorded on a cell phone. But if they had them, Grant probably would have done it.

The last months of Grant's life therefore became a strategic battle: Before he surrendered, the general wanted to provide for his family. Mark Twain gave him the means. The general and the author were friendly, and Twain arranged a blockbuster book deal for Grant's memoirs. Even though Grant refused to include tell-all chapters on his torrid love affair with Robert E. Lee's wife, it was a bonkers deal. Like, Netflix's deal with the Obamas level bonkers. Only Grant had to actually produce something QUICKLY.

He started writing in his New York City home, helped by some editorial aides. But New York City was a hot and smelly place, and if you're having a hard time sleeping AND swallowing, who wants the constant temptation of any ethnic food imaginable at 2 a.m.? Doctors recommended that Grant get out of the city.

This time, Joseph Drexel (of the Philadelphia Drexels) gave him the means. Drexel had a place to stay on top of Mt. McGregor, a few miles from the vacation paradise of Saratoga Springs. (Back then, breathing fresh air and drinking clean water was, in fact, a vacation only rich people could afford.) The building was originally a small hotel, but a much bigger resort hotel had been built nearby, so it was moved downhill a little from the summit and repurposed into a private cottage. Drexel said Grant could crash there for a while, and he even upgraded the property with a new porch and fireplace for the enjoyment of Grant and his family.

If you're taking any lessons from the end of Grant's life, it should be this: Try to have rich friends.

Grant spent his last five weeks at what is now known as "Grant Cottage," and it survives as one of the more unusual presidential sites. The resort hotel on Mt. McGregor -- which accommodated 300 guests and had the astonishing luxury of electricty provided by Thomas Edison -- is long gone. Supposedly it was set on fire by a lightning strike and destroyed in the late 1800s. Met Life acquired some of the property and opened a sanitarium for its employees infected with TB. Then the property became a kind of halfway house for military veterans returning to private life, then the state of New York turned it into a school for the developmentally disabled.

And then it was a prison. From 1976 through 2014, the Grant Cottage was on the grounds of the Mt. McGregor Correctional Facility, a medium-security facility apparently built on the premise that great views and fresh air will make people less felonious. If you wanted to visit, you had to check in at the prison gate and hand over any baked goods big enough to hide a hacksaw. The prison is closed now, with redevelopment plans pending, but that just means there's a spooky abandoned prison on top of a mountain. You drive past it on your way to the cottage and it's truly worthy of Scooby-Doo.

If you're not scared off by the threat of medium-security-prison ghosts, it's totally worth the visit. The cottage is in great shape, and the three rooms you see on the tour are almost exactly as they were when Grant was in residence. The guides are outstanding, and they really set the scene. In his final weeks, Grant could barely speak, but he had to keep working to finish the memoir; when he needed relief from the pain, he turned to "cocaine water." (This may explain the chapter where Grant becomes a winged unicorn.) They still have a jar of cocaine water on the one of the shelves, and being good stewards they are preserving it and will not let you sample it no matter how much you beg. They show you the room where the autobiography was edited, and scraps of many handwritten notes.

They take you into Grant's "bedroom." He couldn't sleep horizontally, because the tumor in his throat would choke him. He sat up in one chair and put his feet up on another chair. And they show you the room where Grant died, just a few days after finishing his memoir. They have the convertible bed where he actually passed away on July 23, 1885, and they even have some of the preserved floral arrangements from Grant's first funeral. It was held right there in the cottage. The clock on the mantel is stopped at the time of his death. Almost everyting in the building is original, as the site has benefited from a series of dedicated caretakers. (One, who they still talk about on the tours, was a Japanese-American woman who had been a childhood TB patient at the sanitarium.)

If you're even slightly able bodied, you should take the short walk through the woods to the scenic view that Grant enjoyed a couple of times in his final weeks. He was carried there, but you should be fine on foot. There's a marker at the spot where Grant looked out at the Hudson Valley. It's now enclosed in a cage because jerk tourists of the Victorian era kept breaking off chips for souvenirs.

And now the most important question: Was the memoir any good? It's in the public domain, so you can read it for free. It's not a "tell all"; instead it's a blow-by-blow account of Grant's experiences in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. There's a little bit on his upbringing, but nothing about his presidency or the many, many rat bastards who screwed him over later in life. The writing is decent, but apparently Grant didn't feel that his impending death gave him license to burn bridges. BOOOOOOOOOO.

Still, it did earn a boatload of money. Mission accomplished.

General Grant National Memorial, New York City

Visited in 2007 and 2012.

Looking up at America's biggest mausoleum.

Some of the very distinctive art in Riverside Park, surrounding the tomb.

A wider shot of Grant's final resting place.

The body boxes at America's most famous presidential grave.

Some of the Civil War themed decor on the interior of Grant's grave.

Getting friendly with the general's subordinates.

Another view of Grant and Julia.

The inspiration for the world's dumbest trivia question is in New York City, smack in the middle of Riverside Park at around 122nd Street. At 150 feet tall, Grant's Tomb is the largest mausoleum in North America. It's our Taj Mahal. Suck on THAT, India!

Grant's Tomb is a fine example of what happens when nostalgia and patriotism are married to newly affordable building techniques. After Abraham Lincoln died, the good people of America scraped together the funds to build him a respectable tomb in Illinois. Then James Garfield was murdered, and the nation decided to honor him with a monument befitting his five glorious months as president! The Garfield tomb (in Cleveland) was under development when Grant died in 1885, and it was going to make Lincoln's tomb look like a hole in the ground.

On the Civil War scale of greatness, Grant HAD to have a tomb nicer than Garfield's. Funds were raised, plans were made, and by 1897 Grant had a final resting place in the GREATEST CITY IN THE WORLD! (At least according to New Yorkers.) Much like Grant, the tomb had its ups and downs, falling into disrepair before a few glorious restorations. Today it's in very nice shape, probably because the federal government operates it, and national park sites are absolutely what the federal government does best.

Grant and his wife, Julia, are in a sunken alcove, making it easier for elderly southerners to walk in, spit on Grant and leave quickly. Their sarcophagi are circled by anti-presidential-zombie charms and five busts of Grant's favorite Civil War generals. Each bust is facing Grant. This creeped me out at first, but after sleeping on it, I now would like Stevie Wonder, Mike Schmidt, Humphrey Bogart, William Shatner and Leeroy Jenkins watching over me in death. Great Americans all.

There are also some nice decorative flourishes showing scenes from Grant's life and mementos of war. And oh yeah, the mummified remains of Grant's servants are in a smaller tomb at 123rd and Riverside.

Grant's tomb is probably more of a monument to his military service than his post-war political career. Grant led the Army for President Johnson, before allowing himself to be recruited as the Republican presidential candidate for 1868. Although he served eight years, he was not a very good president. This was unsurprising, considering that all his past job experience was in either killing people or going broke in horrible business ventures. Congress didn't like him and he basically did nothing for eight years while his buddies got involved in 3,423 corruption scandals. His biggest accomplishment was signing the bill creating Yellowstone National Park. It wasn't his idea. He just signed the paper.

Grant flirted with a possible third term, and his friends made sincere efforts to win him the nomination. But George Washington's precedent prevailed, and Grant skulked off into a brief retirement. It was brief because he couldn't fight a war of attrition with cancer.

Grant was a pipe smoker, but you couldn't really get pipe tobacco on the front. Before a battle, a lackey gave him a cigar, and he was photographed at the battle smoking it. Newspapers ran the photo, and since generals were basically the only celebrities back then, adoring fans sent him thousands of cigars. He started smoking tons of them and ... blammo, throat cancer. Yet another example of the irresponsible media taking down a Republican. Insidious.

In his final days, Grant feverishly wrote his memoirs, hoping that the financial windfall would leave his family sitting pretty. He wasn't wrong. The book (which includes a blow-by-blow account of his maneuvering in both the Mexican-American War and the Civil War) was considered highly readable by 19th century standards.