Presidents: James Monroe

Birthplace: Westmoreland County, Virginia

Visited in 2008, 2015 and 2017.

A 2015 shot of the rapidly evolving Monroe birthplace.

Some of this garden at the the birthsite has probably been displaced by the replica home.

The very simple obelisk. Freemasons, keeping a low profile. Smart.

On April 28, 1758, not far from the modern golf-cart community of Colonial Beach, Elizabeth Monroe squeezed out the kid who would one day become the ambitious, status-obsessed (and slightly above average) fifth president of these United States. In honor of that blessed event, the fine leaders of our republic have seen fit to install a road sign and small parking lot.

Basically, there's growth potential in the James Monroe birthplace industry, but I'll be damned if they aren't doing their best to realize that potential. When I first visited in 2008, the nice little historic markers and the fine mini-obelisk had just been joined by a newly dedicated visitors center. That visitors center was closed at the time, but when I went back in summer 2015, it was OPEN! And there was a bathroom! And some small historical displays!

Even more exciting than that, a replica of the birth home is on the way. They broke ground in 2017, after determining the footprint of the original structure (which is long gone). The most recent news I can find says the replica will be open for business in April 2019, in time for Monroe's birthday. If this trajectory continues, there should be a Monroe-themed amusement park on the site by 2023.

All jokes aside, the site should be a little modest, because the Monroes were a little modest -- at least by Virginia plantation standards. Washington, Jefferson and Madison were born to Virginia farmers with fairly significant land-holdings and a ton of slaves. Spence Monroe, the father of James, had a 500-acre farm and only a few slaves. He grew tobacco, but he wasn't filthy rich. James, one of five children, spent his youth working of the farm and studying.

Both of James' parents were dead by the time he was in his mid-teens, because that was the fashionable thing to do in the 18th century. At 16, James left town to attend William & Mary, then dropped out of school to join the Continental Army in the throes of the revolution. I'm a firm believer that you can go home again, but James Monroe never did. The family farm wasn't really a factor in the rest of the James Monroe saga.

But you gotta start somewhere, right?

Highland, Charlottesville, Virginia

Visited in 2007 and 2020.

A postcard from my 2007 visit to what was then called Ash-Lawn Highland.

A postcard from my 2007 visit to what was then called Ash-Lawn Highland.

Highland in 2020. The white structure was the guest cottage, the attached yellow one was added after Monroe's time.

One of the reconstructed outbuildings at Highland -- it's a nice piece of land.

The outlines of the foundation of Monroe's burned-down home.

Big Game James, dripping wet on a 2020 Saturday.

More of the reconstructed outbuildings at Highland.

This very nice statue of Monroe is hanging out in the Highland gardens.

Ten months after dropping out of school, most of us would be sitting in a basement drinking something fermented. 18-year-old James Monroe was busy getting shot by a foreigner in New Jersey. That's the kind of guy he was -- driven, civic-minded and with a great big chip on his shoulder. Also, they didn't have cable television or swank finished basements back then. That probably helped.

When you think of the Founding Fathers, Monroe gets lost in the shuffle, and that would have pissed him off. Born in 1758 to a fairly well-off Virginia planter, Monroe was orphaned as a teenager, but his uncle arranged to get him into William & Mary at age 16. But when the Revolution came, he ditched school and joined the Third Virigina serving under George Washington.

From that point on he was a professional friend to the stars. He served under Washington at the Battle of Trenton, where he was shot -- he carried the bullet for the rest of his life. He then served at Valley Forge in 1777, where he rubbed elbows with Lafayette, Alexander Hamilton and others. Still recovering from his injuries, he was sent home to Virginia to aid in troop recruitment; while there he studied law under Governor Thomas Jefferson and buddied up with James Madison. One of his childhood friends also became kind of a big deal: John Marshall, Chief Justice of the United States.

Monroe's life was almost non-stop public service: House of Delegates, Confederation Congress, U.S. Senate, envoy to France, envoy to England, governor of Virgina. He helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase for President Jefferson, served as Secretary of State (and War, briefly) for President Madison, and then got the nod as our Fifth President, ushering in what people called the "Era of Good Feelings." Monroe tidied up the loose ends from the War of 1812 and (assisted by his remarkable Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams) asserted the supremacy of the United States in the Western Hemisphere. He goes down as one of the most accomplished diplomats in American history.

But even with all that, Monroe seemed to have a bit of an inferiority complex. He wasn't top-tier Virginia society, and it bugged him. He ran with the big dogs, but he was always rubbing somebody the wrong way. He had long fallouts with Madison and Jefferson. He seemed downright hostile to a lot of the Federalists (Hamilton in particular). In every job he had, he seemed to have a colleague who he thought was a moron.

In other words, James Monroe is my kind of guy.

At least, I think he is. Here's what I wrote after visiting Monroe's home, Highland, in 2007:

"You could call it a poor man's Monticello, but Monticello was actually a poor man's Monticello -- Jefferson and Monroe both died broke. The house itself is relatively tiny, but it's decked out -- years of living the high life in Europe gave the Monroes some fairly rich tastes, and they used their home to wow visitors. (And yet they never had an extra bedroom put on the house -- if you wanted to stay the night, you were sleeping in a room with James.)"

The problem: Highland isn't Monroe's home. In 2016, archaeological digs on the property uncovered evidence of a much larger house which was destroyed in the mid-19th century. For years, the people who owned the property -- the College of William & Mary -- showed visitors a guest cottage and represented it as the residence of James Monroe. I remember asking the guide why the house was so small. I was told that its size was a reflection of Monroe's modesty.

This was a tremendous (and honest) embarrassment. In the years since there's been an above-board rebranding. The estate, once dubbed "Ash Lawn-Highland," is now just "Highland." On their website, they acknowlege the earlier mistake, and they're trying to gussie up the visitor experience with VR and that sort of thing. And to be fair, there are authentic elements, since the guest cottage is filled with a lot of the Monroes' old personal possessions. There's still a lot of value there, but it's really the best reminder ever that history is about narratives, and narratives aren't always reliable.

Regardless, we do know that Monroe lived at Highland for only about 4 years. He was constantly on the move, bouncing around to several different properties, including another Albermarle County dwelling that is now part of the University of Virginia. Plus public service took him to Washington, Richmond, Paris, London and elsewhere for years at a time. He bought the plantation at the goading of Jefferson, who wanted to have his buddies nearby for book clubs and late night slumber parties. (Monticello is about 2 miles away.) But without Monroe's careful supervision of the farming operations, the property was probably a money pit. Monroe sold it off later in life to cover debts. They say he wasn't all that sentimental about unloading the place, because Charlottesville was never his hometown.

Still, I wanted to see it again. I went back in 2020, on a rainy Saturday in the middle of the pandemic. You couldn't go into the guest house, but thanks to archaelogy we know that's not a huge loss. Instead my wife and I had a very nice chat with Nancy, the director of educational stuff at Highland -- she was the historic interpreter on-site that day. She had been there during the big change in 2016 and told us how they managed it.

And they're still evolving the experience. Archaelogy is expensive, but they do hope to uncover more of Monroe's true home (and maybe push aside a mid-1800s structure put up by later owners) if fundraising allows. They're also leaning into the history of Highland's slave population, along the lines of the massive slave history operation at Monticello. From the perspective of attracting visitors, an authentic house is probably the gold standard. But the people at Highland have a blank slate and they seem to be exploring the unusual opportunity that presents.

So, while this isn't the most impressive presidential site, it is an evolving one -- and a pretty cool lesson in thinking about history.

James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library, Fredericksburg, Virginia

Visited in 2008 and 2016.

A very classy bust outside of the Monroe museum.

A little marker reminding us that Monroe owned the block.

Most of us think of the presidents as otherworldly figures, descending from celestial mountaintops in flowing white robes to impart wisdom and deliver ass-kickings to the enemies of democracy.

Just me? Huh.

Anyhow, it's important to remember that presidents were once regular dudes who had to pay the bills. If you're ever in the vicinity of Fredericksburg, Va., cruise on over to the James Monroe museum, which is housed in his former law office in the early part of his marriage.

Sort of.

For many years, it was believed that the building was Monroe's law office, but carbon dating on the bricks indicated that the building is too young for Monroe to have used it. (If you're getting the sense that this is a recurring theme in the James Monroe industry, it is.) But he did own the lot where the museum stands, and his office was somewhere on that immediate block. It might actually be in the wine bar next door. Who knows? Not the people at the James Monroe museum, that's who. But they were still cool.

For $5, you can see a few rooms of Monroe stuff and learn a little bit about the guy. They even have the desk Monroe used while president. It has a secret compartment where Monroe kept letters to Jefferson and Madison, as well as the lyrics to all the power ballads he was writing for his rock band, The Monroe Doctrines.

I never think to save my furniture, and so the desk where I formulated my plan to obsessively visit presidential sites is now in several pieces in a landfill somewhere. Just as well, because I don't think anything purchased at Office Max can ever become an artifact. But I guess that's ultimately up to the Smithsonian. I don't envy the historian who has to restore anything bought at Ikea, especially if the historical figure who owned it ever had to move and just asked his friends to help out. Sigh.

Monroe-Adams-Abbe House, Washington, DC

Visited in 2019.

Behold the D.C. rental of James Monroe.

On the inside looking toward the front door. Kind of nice!

The upstairs parlor, where Monroe met guests after his inauguration.

They have a giant bust of Lincoln because ... uh, well, why not?

Some of Monroe's documents are hanging in an upstairs stairwell.

One of the many Monroe portraits decorating the Arts Club.

A mini event space, just off the original structure.

Even presidents have to deal with contractors.

A closer look at the plaque by the front door. You can see the boot scraper far left.

The United States is the most powerful country in the world, and many people consider Washington, D.C., to be the center of that power. Our government buildings -- gleaming white marble, fit for the gods -- project strength and authority. A lot of people walking the streets at lunchtime are wearing suits, so you KNOW they're making six figures.

It is therefore fun to remember that Washington was once a backwoods craphole, and people hated coming here. The city didn't really exist until the 19th century, when it was cobbled together out of small settlements and farmland. And the construction was not completed overnight. Roads were rutted-out mud pits and farm animals weren't an uncommon sight. What's more, there weren't many homes. When senators and representatives came to the capital on government business, most of them stayed in boarding houses, and a lot of those boarding houses weren't all that nice. The leaders of America shacked up together in the 19th century equivalent of an Extended Stay America.

The Monroes didn't have that option. They were a family of above-average wealth and exquisite taste. After working as an ambassador to the courts of Europe, James wasn't going to share communal bathrooms with dirt farmers from upstate Vermont. Virginia plantation owners had to show people that they had swagger. That's why most of them died hopelessly in debt, but why accentuate the negative?

In 1811, James Monroe returned to Washington as the seventh Secretary of State, answering the call of his sometimes friend, sometimes rival James Madison. The previous secretary, Robert Smith, was squeezed out of office by Madison and Albert Gallatin -- they never really wanted Smith in the first place, but he was one of those appointments that people made to create "regional balance" and "party harmony" in the Cabinet. (The Founding Fathers ran the executive branch like a high school because America is awesome.)

Government buildings were not up to snuff in 1811, and back then a primary job duty of the secretary of State was having fancy dinner parties with diplomats who resented both the existence of the United States and having to live there. So Monroe sought a suitable residence, not far from the center of the action. This couldn't have taken long, as there were only about four nice houses in the city at that time.

He settled on 2017 I St. NW. It was relatively new Georgian-style construction, owned at that time by Gideon Granger, the postmaster general of the United States. Gideon delivered: The home had a lot of rooms, it reeked of class, and Monroe's commute to the White House would have involved very few rutted-out mud pits to soil his fancy secretary-of-State outfits. (It's about 4 blocks from the White House.) Monroe spent a lot of time at his Virginia homes, as government wasn't a year-round thing back then, and face time was useful in preventing slave revolts, etc. etc. But for six years, the I St. house was his D.C. crash pad. He lived there while he was secretary of State, and when he was briefly also secretary of War. He was even there for the first six months of his presidency in 1817, because the White House was being rebuilt after the British burned it in 1814. That burning happened about a month before Monroe took the job at the War Department, so the situation wasn't as awkward as it seems.

It was a very nice home, and a lot of very important people got plastered there. Inaugural balls weren't quite a thing in 1817, but Monroe did greet well-wishers in the upstairs parlor on the day he took the oath. However, it was still a rental, and the tenants kept changing over the years. Ironically, the British legation rented it in the 1820s. Charles Francis Adams, the son of John Quincy Adams, lived there with his wife and son (the great Henry Adams) while serving as a congressman in the early 1860s; he left to become the ambassador to England. The longest-term resident was Cleveland Abbe, who is widely credited as the father of the National Weather Service. He bought the house in the 1870s and lived there for about 40 years.

And collectively, the building now stands as a monument to ... uh, none of them. But it's still totally cool. The owner / operator for the last century has been the Arts Club of Washington. Shockingly, it's exactly what it sounds like. It's a club that promotes the arts. It is not a masonic front that facilitates kinky romance stuff for foreign dignitaries. They host lunchtime concerts, and book readings, and cocktail receptions. Every few weeks they decorate a few of the upstairs rooms with pieces from a working artist. You can walk in off the street, look at them, and buy them if you want. And as long as there's no special events going on, they let you have your run of the place.

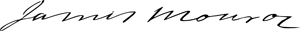

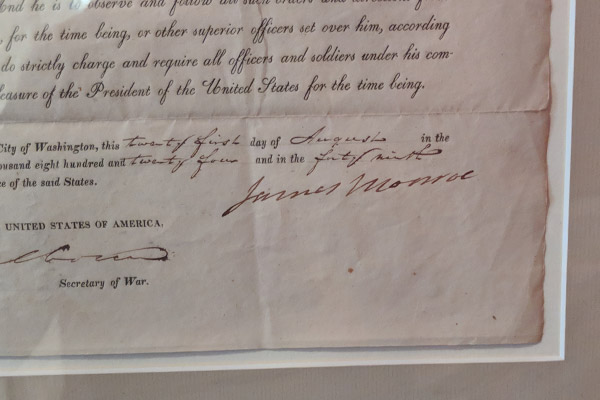

It's nice! The Arts Club acquired some of the adjoining properties, so the facility is bigger than it was in Monroe's time. The building has also been renovated many times over, to add modern plumbing and heating and repair the damage from a fire in the 1960s. There's very little inside the house that dates to the Monroe era, but the Arts Club absolutely celebrates its connection to the fifth president -- moreso than any of the other famous residents. They have several paintings of Monroe hanging inside, and one of the stairwells is decorated with framed copies of Monroe's letters and documents. One is a note to James Hoban, the architect of the White House and also Monroe's estate in Loudoun County.

Beyond that, it's decorated like a clubhouse for rich people, although literally anyone is welcome to visit. So if it's not a traditional historic site, it at least lives up to its Monroe-era purpose: Public entertaining in the nation's capital.

They also have a boot scraper by the front door that Monroe allegedly used, so if you step in anything gross on your way there, be sure to connect with history in a very special way. It's magical to think that you might be removing animal waste from your shoes, using the very same device as a Founding Father. That's what democracy is all about.

Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia

Visited in 2008 and 2019.

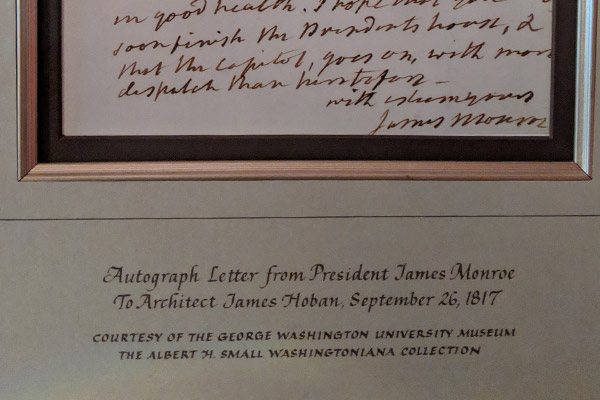

Monroe's birdcage in 2019, freshly painted, with cherry blossoms in full force.

Another angle of the fifth president's second final resting place.

Ironically the birdcage mostly keeps birds away from the president.

James Monroe was a creature of Virginia, but he spent his twilight years in New York. After his wife died, he moved to New York City to live with his daughter and son-in-law. He stayed with them for a year or so before kicking the bucket on July 4, 1831.

Monroe's body was stashed in the family plot of his in-laws, on the south end of Manhattan. No one was bothered by this at the time, but by 1858 -- the 100th anniversary of Monroe's birth -- the people of Virginia were slightly at odds with the people of New York. Proud Virginians (aka racists) began agitating for the transfer of Monroe's remains to the commonwealth, where they could be eaten by worms with a proper appreciation for states' rights.

Monroe's family didn't resist, so the decaying remains of the fifth president were put on a boat, shipped down the East Coast and delivered to the most glamorous final resting place that Virginia had to offer: Hollywood Cemetery. Located in Richmond, it is the most distinctive burial grounds in the commonwealth. At the time, it didn't have any Civil War generals or Jefferson Davis, but it was still a prestigious place to decompose. Thousands of people turned out to watch as Monroe's body was stashed in a new tomb, on a hill overlooking the James River. If we're being honest, it looks like a giant metal bird cage. Monroe enjoyed his place of distinction for only four years. In 1862, John Tyler died. The 10th president -- who perished as a member of the Confederate Congress -- was placed a few feet away from Monroe. Tyler technically has a better view of the river.

If you're into graveyard tourism, you have to visit Hollywood. There are only three locations with two presidential graves: Hollywood, Arlington National, and the Adams tomb in Massachusetts. Hollywood also has the Confederate president, tons of Virginia governors, and assorted military heroes / villains. The natural setting is fantastic.

There's nothing all that momentous about the Monroe tomb, but hey: Giant bird cage. Not bad.