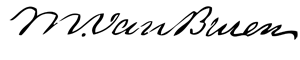

Presidents: Martin Van Buren

Birthplace, Home and Grave: Kinderhook, New York

Visited in 2008 and 2017.

Lindenwald: The world's most intriguing potato farm.

Side door friends are the best! Also that's where the tour starts.

Restoration experts give the wallpaper a 20-year checkup.

Please note that the electric fan isn't original to the home.

Classy living for a foxy president.

A perfect home for entertaining 20-40 of your closest personal friends.

For the Little Wizard, this was where the magic happened. Just kidding, he was a widower.

It's not easy being green, unless you're rich like MVB.

The United States was re-founded in 1789 as a post-partisan paradise. The noble experiment in democracy would have no political parties, largely at the behest of its greatest citizen: George Washington. His countrymen, filled with reverence and respect for their noble leader, refrained from forming parties and avoided the petty squabbles that would surely result.

And they bravely kept that going until [checks notes] ... uh, 1791. That year, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson decided that they hated each other too much, and that George Washington was a smelly old man anyway, and so why not form political parties? The Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans took shape. Battle lines were drawn. Mean-spirited jingles were written. Elections started to get truly, deeply ugly.

And then there was Van Buren. In the 21st century we talk about "digital natives"; but in the history of American presidents, Van Buren might be the first political native. He was born in the United States, as opposed to the colonies. By the time he came of age, political machinery and political methods were already in place. His entire career was rooted in the new system, he understood the new system in ways that many elders did not, and (most important) he played for the love the game. Martin Van Buren was poised to be the Lebron James of the national political scene, only 5'6" and with red hair.

The only reason we don't hear more about him? His presidency truly, deeply sucked.

But any lover of American history should make a point of visiting Kinderhook, to get the full Martin Van Buren experience. He was born in town on December 5, 1782. Van Buren was the son of a tavernkeeper, and while the tavern where he was born is long gone, the site is sanctified with ... well, a historical marker on some jerk's front lawn. By most measurements, the Van Burens were probably poor, but the tavern was where people came to talk s*** and talk politics. Even though MVB started out speaking Dutch -- English was his second language -- he was sucking up gossip and information from people traveling the post road between New York and Albany.

And that's how you get to be a player. (That or owning a Ferrari, but the automobile hadn't been invented.) Van Buren studied to become a lawyer, but from a young age he was clearly a career politician. He was active in campaigns for Democratic-Republicans, set up his own faction in the New York branch of the party, and started the morally fluid wheeling and dealing that we now expect from all politicians. Van Buren enjoyed pulling strings, but he eventually took on big jobs for himself. In the early 1820s, the state legislature sent him to the United States Senate, and once he was on the national stage there was no turning back.

Van Buren took all the lessons he had learned at the state level and applied them with brutal efficiency. He identified Sen. Andrew Jackson as a highly electable candidate, and did as much as any man to engineer Jackson's election in 1828; I'll spare you the gory details, but Van Buren was one of the primary architects of a new kind of political campaign. He rewrote the rules of the game and became Jackson's right-hand man. His relentless pragmatism left him as the natural successor to Jackson in 1837.

MVB's birthplace ... on some guy's front lawn in Kinderhook.

That home in the back is NOT the birthplace, but it's more interesting than the sign.

Kinderhook Reformed Cemetery: It's a pretty simple grave for a big shot.

The people maintaining the cemetery keep Van Buren's grave on point.

A close-up of the inscription.

I wore my finest Greg Norman shirt to honor our greatest political shark.

And then the economy collapsed. Van Buren took the blame, and he became America's third one-term president when the Whigs Party turned his own campaign tactics against him. It had to hurt when William Henry Harrison moved into the house that Martin Van Buren built. But at least he had another home to worry about.

In 1839, Van Buren went back to his roots and bought property in Kinderhook. When Van Buren was a kid, it was the estate of some local big-shot judge and the top status symbol in town. Van Buren bought it for his post-presidency estate to let everyone know that he was the biggerest shot. According to the excellent Park Service guides, MVB probably had a chip on his shoulder from growing up poor. It must have been a very big chip. Because when Van Buren bought the home, it had something like 18 rooms. By the time he was done it was up to 36, with an Italian-style tower, which would help you keep a lookout in case a mob of poor people ever tried to rush the place. And where did the money come from? Van Buren was a good lawyer, but my guide in 2017 suggested that his fortune came from real estate spectulation surrounding the Erie Canal. If you had insider information on its construction, which Van Buren clearly did as one of the biggest guys in New York politics, you stood to clean up. We'd find this horrifying today, but it was pretty much par for the course in the early 1800s. It was a zanier time.

The house is sprawling, airy, high-ceilinged ... and luxurious. Guides tell me that MVB didn't decorate, leaning on the talents of ladyfriends. But he was a gadget freak, and he installed unbelievable luxuries like a coffeemaker and a flush toilet. (Bear in mind that in the 1830s the flushing mechanism involved four Irish servingwomen, a rubber hose and a considerable amount of cursing.) He had elegant and sophisticated decor throughout his home, including a beautiful green parlor. (The color green was first invented in 1836, so at the time that would have been a VERY expensive room.) On my 2017 visit, I rolled up an hour before closing time and had the pleasure of a personal tour; on that day historic preservation experts happened to be examining the stunning pastoral wallpaper in the main hall; it was a treat to see the brilliant colors and details fully illuminated. Van Burn had a reputation as a dandy and the Italian-made ironing press to back it up. He entertained all the Albany big shots and anyone else who cared to stop by. (Notable guest for 1849: Henry Clay, who almost definitely indulged Van Buren's favored pastime of playing cards, and probably bet a s*** ton of money in the process.)

My favorite room is Van Buren's study, which was the de facto nerve center for two more presidential campaigns. MVB tried to secure the Democratic nomination in 1844 but fell short. And in 1848 he had a late turn toward idealism, allowing himself to be drafted as the candidate of the anti-slavery Free Soil Party. He kept his office decorated with political cartoons ... that mocked him. The guy loved the game, and apparently wasn't bitter about his losses. He just looked to the next battle.

Van Buren lived 20 years at his estate, which he called Lindenwald. Supposedly those were the the happiest years of his life. He built rooms for all his kids to come visit, as he was a widower from his early 30s and never remarried. When he wasn't trying to rule the world, he could focus on the fact that Lindenwald was a functioning farm. Long before Jimmy Carter was famous for growing peanuts, the eighth president grew potatoes. Probably in a desperate attempt to lock down the Irish-American vote. (One of Van Buren's sons moved in for a while to run the agricultural operation, but bailed out after a few years of "gentleman farming.")

Van Buren also met his end at Lindenwald, probably resting in his own bed. When I was there in 2008, they had a cane resting on the bed that was a gift from "Old Hickory" Andrew Jackson; each knob on the cane has a letter on it, spelling Jackson's name. The way the room is set up today, there's also a picture of Jackson on MVB's bedroom wall, directly opposite his bed. It's refreshingly creepy.

And to keep things tidy, they buried Van Buren in Kinderhook as well. He's about two miles away from Lindenwald, in the Kinderhook Reformed Cemetery. It's a modest marker -- just a small obelisk with some worn engraving. After seeing the house, I was expecting something a little more brazen, but there were no fog machines, no laser light shows, no nothing. Sigh.

One final note: if you have the chance, always talk to your park rangers. And don't just pester them with questions about history. Get to know them. At Lindenwald, a brief conversation with the guy in the visitor center uncovered the fact that he has tried to do stand-up comedy at a local open mic AS MARTIN VAN BUREN. He tried both period jokes ("What is the deal with William Henry Harrison?") and some of Van Buren's takes on modern politics. Folks, that takes BALLS. God willing a tape of this will surface one day. Internet, do my bidding.

Decatur House, Washington, DC

Visited in 2019.

Steps from the White House, you'll find one of D.C.'s most historic homes.

The back entrance. The slave quarters are the white structure on the left.

The front parlor. I think the sabers on the mantel are Decatur's.

The downstairs dining area.

Latrobe's classy entry, with a double-wide door onto Lafayette Square.

In an upstairs parlor, the late Stephen Decatur gets to enjoy his view.

Looking along the side of the slave quarters toward the side of Decatur House.

Stephen Decatur was a great man. As a naval officer, he became one of the country's first post-Revolution military heroes. He had a household name, powerful friends, and money to burn. He could have been president.

The only hitch was his untimely death. Decatur had beef with Commodore James Barron, whom he once considered a friend. Barron had surrendered a ship to the British in 1807. Decatur, feeling that Barron had rolled over too easily, participated in the court martial that kicked Barron out of the Navy for five years.

And if you're young, rich and famous, why not poke the bear? When the War of 1812 was in full swing, Decatur criticized Barron for not returning to military service. He kept on antagonizing Barron, until finally Barron challenged him to a duel in 1820. From a spectator's perspective, it was a great duel -- both men got shot. But only Decatur died. He did not have children, but he was survived by his wife.

And oh yeah, he was also survived by his kick-ass house! Decatur was a big shot in the early years of Washington D.C., when the city was little more than muddy roads and middle-aged white guys in fancy clothes, ravaged by venereal diseases contracted at the local boarding houses. Decatur wanted a great home for entertaining, so he took some of his sizable fortune and built one. For an architect, he got Benjamin Latrobe, the designer of the Capitol. For a location, he locked down a nice piece of land right next to the smoking ruins of the White House. The president's mansion was still recovering from the extreme home makeover of Admiral Cockburn in 1814, but the rebuilding was under way.

The home was a three-story brick structure in the Federalist style. At the time, it would have jumped out of the landscape: There was no "Lafayette Square," and the only buildings around were the White House and St. John's Church (both of which are still there). It was swanky, and Decatur got to enjoy it for all of 14 months before learning that dueling is a bad idea.

Today you can tour the home thanks to the good people at the White House Historical Association. That organization, which is fanatically devoted to both the president's residence and the development of high-end Christmas tree ornaments, owns the Decatur House and a few of the adjoining structures. The whole complex is their office, with the Decatur House is the flashy showroom they use for classy events.

It's cool. The house is one of the oldest surviving residences in the District, ranking up there with the nearby Octagon House and the Monroe House. Latrobe did some nice work, creating a pleasure palace with big windows, high ceilings and lots of rounded walls. The WHHA does a nice job of straddling the centuries; they show you rooms that would reflect the Decatur era, plus spaces that were modified by later occupants.

Which gets us to the presidential part of our story! Susan Decatur saw the value of a good real estate investment, and she also probably saw that as a woman in the 1820s she didn't have a lot of other revenue streams. So instead of staying in the house, she rented it out to people who wanted to act important. It was awesome for diplomats, because the diplomacy of the early 19th century was 80 percent dinner parties.

As such, the Decatur House was the D.C. rental of three consecutive secretaries of State. The first was the legendary Henry Clay, a 47-time presidential candidate and one of the greatest legislators in U.S. history. The second was Martin Van Buren, who later became the eighth president. The third was Edward Livingston, who I don't know anything about, so forget him.

Van Buren got the job the old fashioned way: Andrew Jackson owed him one. Van Buren effectively coordinated Jackson's presidential campaign in 1829 and was particularly helpful in getting his home state of New York on the side of Old Hickory. At the same time, Van Buren orchestrated his own election as governor of New York, but he kicked that job to the curb when Jackson offered the most glorious post in his cabinet. By most accounts, Van Buren was a pretty decent secretary, knocking out a few treaties.

And don't forget the parties. Van Buren was well-off, well-dressed, and well aware that style points counted. He probably made Decatur House in to party central, because parties were the primary means of transmission for political gossip and news. The dude was an operator.

So naturally, Washington's social scene is what ended his tenure as secretary. Van Buren quit his job as part of "the Eaton affair," a now-forgotten scandal where a the real housewives of D.C. wouldn't stop gossiping about the wife of War Secretary John Eaton. The bitchfest focused on the fact that she had married "too soon" after the death of her first husband, and was therefore probably maybe having an affair with Eaton when the first husband was alive. The Nene Leakes of this scenario was Floride Calhoun, the wife of the vice president. This didn't sit well with Jackson, who firmly believed that his own wife was driven to an early grave thanks to the stress caused by rumors about her.

Yes, this is hilarious.

The dynamics in Jackson's cabinet became so awful that Van Buren (an Eaton supporter) took one for the team, offering to resign. That gave everyone else in the cabinet the cover they needed to resign -- only the postmaster general stayed -- and allowed Jackson to weed out anyone friendly to Calhoun. Van Buren was going to be shifted into the role of ambassador to England, but Calhoun blocked the nomination. Instead, Van Buren wound up as Calhoun's replacement in Jackson's second term.

The WHHA tour doesn't go too heavily into the Van Buren years -- the house just has too much history to cover. (For example, it was also the residence of Vice President George Dallas.) But they do toss out one interesting bit when you tour the slave quarters.

First off, it's unusual that an urban dwelling HAD extensive slave quarters, and it's SUPER unusual that they survived to the modern day. But there was definitely a structure for housing the enslaved, just a stone's thrown from the White House. The story they home in on is that of Charlotte Dupuy, a slave of Henry Clay. She had been promised her freedom by a previous owner, who sold her to Clay. She believed Clay had to honor the promise, and she sued him for her freedom while he was living at Decatur House. The case wasn't resolved by the time Van Buren replaced Clay, and Dupuy refused to return to Kentucky with Clay. Instead she stayed on as Van Buren's servant, and Van Buren paid her.

Dupuy ultimately lost her case and was forcibly returned to Clay, so it's not a happy story. I wonder about the politics of it all. Van Buren wasn't an abolitionist until later in life -- remember, his biggest political ally was a plantation owner. But he was one of Clay's biggest opponents. Did he hire Dupuy because it was the right thing to do? Or did he do it to create a headache for a rival?

Beats the hell out of me! But it's an interesting story, and I'm sure that one day the Bravo network will do it justice.