Presidents: William Henry Harrison

Birthplace: Berkeley Plantation, Charles City County, Virginia

Visited in 2009.

It's a brick house. Mighty. Mighty.

See, I improved the first picture by adding me to it.

And you think it's tough to please YOUR parents.

The same house, from the side. Indian-resistant architecture was a theme in WHH's life.

The magnificent lawn, with its ... uh, grass.

Getting a black powder demonstration at the REAL Thanksgiving celebration.

The James River, one of the aquatic highways for Virginia's plantation economy.

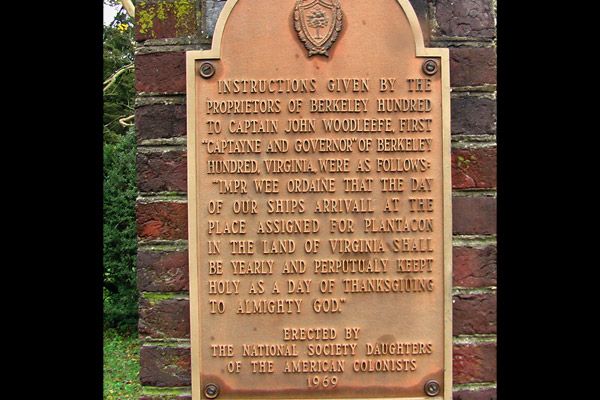

This plaque pretty much settles any controversy.

A hitching post. Because, why not?

You know the First Thanksgiving: weatherbeaten Pilgrims sit down with generous Indians, and two vastly different peoples share the fruits of their labor and let celebration bridge the vast gaps between them.

WRONG!

America's REAL First Thanksgiving took place before the pilgrims even landed. On December 4, 1619, not far upriver from Virginia's Jamestown, John Woodleaf led ashore two score settlers from the good ship Margaret. They knelt to the ground and gave their thanks to divine providence. There were no Indians; there were no buckle hats. Per their charter they would celebrate that landing each year, in the settlment at the modern-day site of Berkeley Plantation.

It was a glorious and poignant tradition that survived all the way to 1622, when they sort of had to stop because Indians massacred about a third of the white people in Virginia. The moral here is that a little pumpkin pie goes a long way toward making Indians happy.

Still, even if Massachusetts got it right, Virginia got it first. And any true history buff knows that FIRST IS WHAT MATTERS! Berkeley celebrates the Original Thanksgiving with a festival the first Sunday of every November, and I was able to use that awesome pretext to trick some friends into visiting the birthplace of ... wait for it ...

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON! See, you thought this was about Thanksgiving, but I turned it into a president thing. You'd think you'd learn.

But first we gotta talk about this festival. When I say "festival," you're thinking big, right? Maybe some kind of food pavilion? Maybe someone on a horse? Maybe kids carrying balloons, and local artistes trying to sell ugly homemade jewelry at an endless series of booths, and clowns painting faces?

Well you could not be more wrong. A festival is 30 people sitting in folding chairs under a tent in the rain, watching the following program:

- Some kind of choral thing.

- A "re-enactment" of the original Thanksgiving landing, minus any kind of boat. Now, if you just got off an (invisible) boat carrying 40 people after two months, you'd be pretty excited, right? You might hump a tree, or at the very least convey unbridled joy through your voice, right? Nope! I now know from the reenactment that the first thing you do when you land is take attendance, then stand in a line talking in a monotone until the guy in the minister hat tells you to kneel. I'll say this: those guys kneeled in the mud, in period costumes that are probably dry-clean only. That's love.

- A speech from a retired Virgina state senator. I liked this guy.

- A guy playing "Taps" while hidden behind a bush (more on this in a minute). Why was he behind a bush? I'm not exactly sure. Maybe the acoustics were better, or the guy was really ugly. I just don't know. The bush was blocking my view.

- A raffle drawing.

- Indian dancing. I wasn't paying too much attention at this point, so I did sort of miss how the "friendship dance" fit into the storyline of Indians killing so many people that the settlement had to be abandoned. But I am generally pro-friendship.

They had more planned at some point. Mike of the James River Black Powder Club not only gave us a fine demonstration on period weaponry, he also gave us the straight dope: the rain had sent a few people packing. Crowds were light thanks to a steady downpour for most of the morning, so some of the other "living history" stuff was shut down once the media was gone. Given the chance to make my own rag doll, or perform an amputation without administering anesthesia, I might have had a blast; as it was, I had a fine time, but I don't think I'd plot a return visit until the 400th anniversary in 2019. That party is going to be OFF THE CHAIN. Really, they're going to have the blacksmithing demonstrators make a chain, then take the party off it.

There's so much more to Berkeley than festivals, though! It's one of the oldest estates in America, and as such, everything interesting in United States history happened there first. Such as:

Taps. Dan Butterfield wrote "Taps" while at Berkeley during the Civil War (McClellan camped the Union army there around 1862). The tune, meant as a sorrowful expression of what a huge sissy McClellan was, has survived through the decades. As a former Boy Scout bugler, I can testify that this song is so mournfully powerful, that merely playing it will have many a grown man shout: "Dave, why is your damn kid playing the ****ing bugle at 7 in the morning?"

Bourbon. The first bourbon whiskey in America was made at Berkeley.

There you have it. The two most important firsts in U.S. history, at Berkeley.

And let's not forget the Harrisons, who turned that godforsaken hellhole into a thriving center of commerce. Benjamin IV built the fine mansion, and Benjamin V (buried on site!) manned up as a public servant and signer of the Declaration of Independence. William Henry, who spent a great deal of his life avenging the massacre of 1622, was born in the mansion, probably in an upstairs room. He left Virginia at a young age for the raw, wild sensuality of Ohio and Indiana, but the house (restored in the 20th century to its 1700s appearance) still has some nice tokens from his life, like a paisley shawl. You might say, "how could a military hero wear a paisley shawl in public?" And you'd be right to say it, because Harrison didn't. With a little less pride, he might have bundled up in 1841 and not died.

According to our guide, WHH might have actually been at Berkeley to compose the Inauguration Day speech that famously killed him. But I'm not going to list that as a fact, because our guide was terrible. He admitted he hadn't given the tour in a few months, he completely blanked out on about six occasions (in a FOUR ROOM TOUR), and then gave up in every instance with: "Oh well. Any questions?" I did have questions, but I'm not too confident the answers we got. The guide mentioned that the home had brick walls three feet thick. When I asked why, he said "protection from Indians." You know, Indians, with their heavy artillery. Did I mention this was a $10 tour?

Still, the house is nice if unspectacular. It was visited by every president 1 through 10, not to mention Lincoln. And it's rare these days to find a plantation tour that is willing to completely ignore slavery. I particularly enjoyed the portrait of young William hanging downstairs. He was movie-star handsome in his early years, and the portrait showed him in the uniform of a Lt. Major General. The problem is, he wasn't that rank until a much later age. Apparently he did not like sitting for portraits, so when he refused to do so later in life, they got the painter to Photoshop an older portrait. He slapped the fancier uniform right on top of the old one. Heh.

Then on the way home we ate at Cracker Barrel. History is awesome.

Grouseland, Vincennes, Indiana

Visited in 2011.

It's a fort! It's a house! It's two, two, two things in one!

You can see the defensive elements, such as the basement gun ports and the curved walls.

A very classy home, considering it was the middle of nowhere.

The many bumperstickers of my guide's car. I liked that guy a lot.

A man's home is his castle. When building his governor's mansion in Vincennes, William Henry Harrison decided to take that literally.

There are gun ports around the entire house at ground level. Most walls were solid brick construction at least a foot thick, even though the town was mostly log construction. The window shutters were 2-inch-think slabs of wood capable of stopping bullets. There's a lookout tower in the attic and the walls facing the Wabash River are curved outward to improve the range of vision. The basement has an armory, a well and an old-school septic system (a French drain) to dispose of sewage in the event of a siege. There's enough floor space to sleep a bunch of townspeople in an emergency. He didn't rig a murder hole, but only because huge cauldrons of boiling pitch might damage the carpets.

With a home like that, a man could screw over some Indians! In the early 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson put him in charge of the vast Indiana Territory, Vincennes was a white raft floating on an ocean of wilderness. More settlers were on the way, and the feds wanted to secure any mildly dubious lands claims with the indigenous inhabitants.

Harrison had a flair for it. The Constitution didn't really anticipate the administration of federally held territories, and so governors could act like dictators as long as they got results. He would find sympathetic chiefs, then negotiate ridiculous land swaps that those chiefs weren't really authorized to make -- as the guide at Grouseland put it, it was like paying the mayor of Akron to sign over Ohio. Harrison also looked the other way whenever settlers got needlessly violent with the locals. Hostilities were a definite possibility, and Harrison probably had some personal bugaboos, too: his birthplace, the Berkeley plantation in Virginia, was the site of pretty significant massacre of settlers in the 17th century. The home Harrison was born in had brick walls two feet thick, so at least the family was mellowing over the generations.

Which isn't to say that Grouseland has no charm. When he wasn't eradicating the legacy of an entire race, Harrison had a few dinner parties. The room where fairly significant chunks of the Midwest were snapped up also doubled as a swanky parlor for chatting up guests. Harrison had a reputation as a regular, approachable dude -- he dressed neatly, but not like a rich prig; he was happy to welcome regular Joes into his dining room; and he was famously beloved by his troops. One marker on the property said Grouseland was the birthplace of "Hoosier hospitality," which is really just Virginia plantation culture moved 600 miles west. The building has a frontier elegance about it, and since Harrison's wife was constantly popping out children, it's also homey.

But the Indian stuff is what makes it sexy. Grouseland is where Harrison laid the foundation for the legend of "Old Tippicanoe." He stepped on enough toes that eventually Tecumseh and the Prophet called shenanigans. There was a famous showdown at Grouseland, with Tecumseh getting into a shouting match with governor. And as the nearby settlement founded by the brothers started to grow, Harrison's paranoia got the best of him. He waited for a time when Tecumseh would be out of town, raised a militia and marched north to Tippicanoe to burn the Indian village. Classy.

Now, I ask a lot of questions on any given tour. But there are people -- middle-aged pudgy white men with woven belts, mostly -- who prefer to quote history lessons to the actual guides. This is because no one will talk to them about their hobby, they are not getting the graded validation of a classroom environment, and they haven't figured out that blogging is a good release. Such a man was on my particular tour, and on hearing this story, he lectured the guide for about a minute before closing with, "You have to admit the Indians had it coming."

At that point, the tour guide admitted that he was half Indian. Specifically, the kind of Indian whose land Harrison stole.

My enjoyment at belt guy's awkward reaction doesn't really justify three centuries of oppression and discrimination, but hey -- make as much lemonade as you can, right?

FUN GROUSELAND FACTS!

- There is some original furniture in the building, but many decorations aren't exactly accurate; the D.A.R. owns the house, and according to the guide, the little old ladies who decorated it went a little overboard. For example, it is highly unlikely that William Henry Harrison kept five tea sets and kitten-embroidered pillows on his bed.

- Tecumseh predicted the 1811 New Madrid earthquake to other tribes as a symbol of his power. The plaster in two of the Grouseland guest rooms still has cracks from that quake. SUCH WAS THE TERRIBLE WRATH OF TECUMSEH!

- Indiana was supposed to be free territory, but Harrison brought along slaves when he moved to Grouseland. When this caused concern among some human-rights-minded settlers, Harrison solved the problem by declaring his slaves to be honorary Indians.

- Harrison's hat and saber from Tippicanoe are on display at Grouseland. He eventually left the home for military service in the War of 1812, and had caretakers operate the building as a bed and breakfast for people who didn't mind the risk of being scalped in their sleep.

- The name of the house comes from the birds that were plentiful in Indiana at the time; grouse was one of Harrison's favorite meals. His grandson Benjamin Harrison took this to heart in naming his first home, Funnel Cake Junction.

- Despite Harrison's worries, there were never any Indian attacks on the building. However, 7 teenagers were shot trying to egg the house on Halloween 1808.

- Harrison wasn't a particularly brilliant military strategist, but as the father of 10 children, he did wage a very effective siege on his wife's uterus.

Grave: North Bend, Ohio

Visited in 2006 and 2013.

For such a short presidency, the guy had a huge tomb.

Patriotic stone carvings? Check.

The approach to Harrison's final resting place.

Do the bars keep us out? Or do they keep Harrison in?

A peek through the bars at Harrison's eterna-morgue.

Congressional Cemetery: Bonus pic of the D.C. vault that was Harrison's not-quite-final resting place.

It takes a big man to admit his mistakes, and I made one in 2006. I was doing a stand-up gig in Cincinnati, my brother Dave came to visit me, and we went 20 minutes west to see William Henry Harrison's tomb.

No, we haven't gotten to the mistake yet.

After bumming around in Indiana territory for a few years, W.H. Harrison backed up a state and bought a farm in North Bend, Ohio. He was elected to Congress while living there, and when he ran for president his campaign touted his rustic log cabin living along the Ohio River. It was a total scam, since Harrison replaced the initial log cabin with a mansion. He was a rich dude. But why argue with success?

These days, Harrison's tomb is arguably the most interesting thing in North Bend, which has a population of about 900. It has a very nice monolith, it's on the side of a hill, and it overlooks the river. Harrison wanted to be buried there, and his body was transported there from D.C. by a series of black-draped barges. (Fun fact: For the first few months of his afterlife, Harrison was kept in the "public vault" at D.C.'s Congressional Cemetery. The same structure was also the temporary resting place for John Quincy Adams and Zachary Taylor.) His family gave the tomb to Ohio in the 1870s in exchange for the states' promise to keep it nice. I've seen worse presidential graves. We checked it out, took some silly photos and went back to Cincy to do something else that was probably equally cool. It's how we roll.

The mistake: We forgot about Benjamin. The Harrison family was in North Bend for a while, and William's grandson was born there in 1833. The Ohio historical mafia put up a very nice sign to commemorate the blessed event, and we didn't even think to look for it. Every time I stared at my presidential "to do" list over the next seven years, that was the dagger in my heart. So close, yet so very far.

That's why I vaulted out of bed at my moderately cheap hotel on June 1, 2013. The night before, I had driven until 1 a.m. to get to the Cincinnati region. That Saturday, it was like waking up at 4 a.m. on Christmas morning, only I wasn't a kid, and my family wasn't there, and there was no promise of making memories that anyone would want to share, and instead of a nice breakfast casserole I had a Rice Krispie treat that I bought at a gas station the day before.

The Benjamin Harrison marker is easy to find. It's at the intersection of Washington and Symmes (the maiden name of Benji's grandmom) in a residential neighborhood, where it quietly drives up the property values ALL DAY LONG. No one was on the street that morning, so no one saw the single tear roll down my cheek as I stood there and contemplated the career of Benjamin Harrison in all its glory.

Once I had composed myself, I decided to revisit William's tomb; they put in a new parking area since 2006, which made this visit all the more special. Other than that, no real changes to report. He's still dead.