Nerdcation 2013: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee

When I was a single man, I went where I pleased and made no apologies, unless I accidentally spilled something or burped at a bad time. As I drove around the country, I saw thing things that I wanted to see, I stayed as long as I wanted to stay, and I slept in the motels where I wanted to sleep. I ate a lot of peanutbutter sandwiches, and when I didn't have a knife to spread the peanutbutter, I used my plastic motel key cards. Just like the pioneers.

Which is to say, I was spoiled. You can't travel that way your whole life, and once your vacations start to involve spouses, significant others or friends, you have to make concessions. Some people won't be comfortable staying in motels with visible bullet holes in the wall. Others won't understand the joy of driving 100 miles out of your way to see a metal sign marking the site of the now non-existent house where someone was born 150 years ago. As painful as it may be, you have to let those things go.

But every now and then, the universe will let you get a fix. At the end of May 2013, my wife had an out-of-town bachelorette party to attend. At the same time, I was wrapping up a huge project at my day job, and they told me to take a couple of days off, for the mental health of the office.

It was a perfect storm. With about 12 hours of planning, I embarked on a second Nerdcation. These pilgrimages involve a lot of travel in a very short time. The destinations are such that no reasonable person would ever visit them. According to the sacred texts, no motel can cost more than $50 a night. And by the end, you shall understand in your heart what it means to be American. Either that, or you will appreciate the extremely long odds that anyone bothered to marry you.

Henceforth, the notes from Nerdcation 2, a four-day, one-man journey covering 2,000 miles and involving a lot of peanutbutter sandwiches.

May 30, 2013

The Bachelor

Consider the legend of America's greatest president, contrasted with the story of the man considered the worst. Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin in the wilderness, had some mildly adventurous formative years, trained as a lawyer, and ended up president of a fractured nation. James Buchanan was born in a log cabin in the wilderness, had some mildly adventurous formative years, trained as a lawyer, and ended up president of a fractured nation. And Buchanan did it first.

History is hilarious, and if more people got the joke, Mercersburg would be raking in the tourist dollars. For now the lines at the Buchanan historic sites are manageable. You can roll up to the James Buchanan Pub and Restaurant at 2 p.m. on a Thursday, and -- get this -- it won't even be open!

Which is understandable. There's not much going on in south central Pennsylvania these days. Mercersburg is surrounded by sleepy farm country, and major highways don't take you through the town. There's a famous school there -- Mercersburg Academy was actually the alma mater of Jimmy Stewart, and Harvey the invisible rabbit -- but it's not a thriving metropolis.

In 1791, it was a different story. The wagon road ran straight through the town, which was a significant outpost on the journey west -- at a time when everything left of Pittsburgh on a map had pictures of dragons. James Buchanan Sr. had a trading outpost at a spot he called Stony Batter, where people could stock up on the supplies they would need to fight Indians, feed their horses or satisfy their urges for 18th-century erotica. There might have been Slim Jims, too.

Buchanan was born at Stony Batter, a few miles from Mercersburg, in some kind of log cabin. No one realized he would be famous, so they didn't bother marking which cabin was the sacred one. Today, a cabin from Stony Batter has been transported to the grounds of Mercersburg Academy, where many generations of prep students have spied it from the lacrosse field and asked, “what the **** is that?†Some have even gotten to second base against it. It might be Buchanan's birthplace, but it also might have been a storage shed for the 18th-century equivalents of glow-in-the-dark condoms, impotence cures and Twinkies. Either way, it's a fine and historically valuable structure, and if you want you can drive straight on to campus and stare at it for a few minutes -- no charge.

Cove Gap: The humble origins of the (maybe) worst president.

Cove Gap: The secrets of the pyramids revealed.

Mercersburg: The site of ye olde boyhood home. Now a restaurant!

Mercersburg: The site of ye olde boyhood home. Now a restaurant!

The alleged birth cabin, on the grounds of Mercersburg Academy.

Mercersburg: Nobody was home. Sigh.

Stony Batter itself is now the home of a state park and a small pyramid that marks the alleged site of the birth cabin. The cash to set it up came from Harriet Lane, Buchanan's niece; as he had no children or wife, she was the sole protector of his legacy – a fun job, whereby she had to convince people that her uncle was not the worst president who ever lived. When she died in 1903, she left behind the funds to set up both the birthplace marker and a statue in Meridian Hill Park in Washington. Meridian Hill Park for a time became Malcolm X Park, and it was an open air drug market during the crack epidemic, so a stone Buchanan probably oversaw all kinds of stabbings and compensatory sex acts. Just like the good old days.

The Buchanans moved by 1796, heading a few miles south to the civilized confines of Mercersburg. The roads there were probably still dirt – but a more orderly kind of dirt. James would spend the next 10 or so years there, before shipping off to Dickinson College and a life of adventure; he would be a state and federal legislator, an ambassador and the secretary of state before Democrats finally decided it was his turn to run the country. It all worked out great, except for the start of the Civil War.

The aforementioned Pub and Restaurant is in the building where the Buchanans lived in Mercersburg, so there's the tantalizing possibility of having a beer in the very place that 10-year-old James Buchanan has his first beer. You just have to get there between 5 p.m. and 9 p.m. on a Friday or Saturday. All other times, the restaurant honors Buchanan's legacy by doing nothing, while frustrations mount among the throngs of thirsty history nerds on the sidewalk.

OK, it was just me. But I'm a one-man throng.

May 31, 2013

Yes, We Canton

Objectively speaking, the end of William McKinley's life was more interesting than the beginning. A mentally unstable anarchist took him out of this world, while uptight Methodists brought him into it.

Still, you gotta start somewhere. McKinley was born in 1843 in Niles, Ohio, north of Youngstown. He was the seventh of nine Irish/Scottish halfbreeds -- a mix that cemented his fighting spirit and hatred of underwear. His family had come to Ohio from Pennsylvania, and despite that horrible decision they seemed to prosper in the iron-working business. The town was pretty new, and the McKinleys had a lot pretty close to the Mahoning River.

Even back then, parents moved to find better school districts. By 1852, the family had departed to Poland, south of Youngstown, so McKinley could go to some hoity-toity academy there. Nothing terribly interesting has happened in Niles since then. The iron-working industry has moved elsewhere, and it has been replaced by the dilapidated-motel-not-too-far-off- I-80 industry. My room in the Economy Inn had a very nice sign reinforcing that anyone using the room for more than 15 minutes would have to pay for a full night, and that the "no drugs in the room" policy was fairly strict. People clearly respected the sign, because the probable meth addicts seemed to be hanging out in the parking lot. The next morning at the breakfast buffet, someone stole two gallons of orange juice.

The recreation of McKinley's birthplace, and also a Dollar General.

Another view of the replica birthplace.

Approaching the Memorial Library, a few blocks from the birthplace.

The McKinley statue at the Memorial Library.

McKinley relics at the museum attached to the memorial library.

But let's not smear the whole city. The downtown is cute enough; like a lot of small towns in the Midwest these days, it's quaintly unspoiled by economic development. I drove in, found a parking space and went in search of the McKinley Birthplace on Main Street. You can't miss it. It's right next to the Dollar General.

It might break your heart to know that, even on a Friday morning, it was closed. I was alright with it. The home is actually a reconstruction; after the McKinleys left town, the original building became a general store, was split into two pieces, got moved around and eventually burned to the ground in the 1930s. The eight-room, two-story replica is on the same site as the original house, and it's an architectural match. But there isn't any significant McKinley swag inside. The decorations are just a best guess, and if you've seen the outside you've seen the best part.

So the real show is down the street at the McKinley Memorial Library. You can't miss it. It's on the other side of the Dollar General, and it's the only thing in town that looks like a Greek temple. About a decade after McKinley was recalled by God, a wealthy industrialist from Niles thought it might be nice to honor the city's most famous son. He got the fundraising together, and in 1917 the finished structure was dedicated -- as its inscription says, "free to the people."

Even at that price point, there wasn't a big line at the door. But it's really a very cool structure. There's a colonnade facing the street, and when you walk through it you're in a courtyard with a nice-looking, dignified McKinley statue in the center. (Dignified isn't easy to pull off with McKinley, who was sort of on the beefy side in his later years.) He surrounded by a semi-circular wing of busts depicting some of his contemporaries and friends -- Bill Taft, Mark Hanna, Teddy Roosevelt and Andrew Carnegie among them. One side of the courtyard has the entrance to a public library, and if you go in and stand awkwardly by the entrance for a few minutes, they'll figure out that you want to go to the museum on the other side of the courtyard.

"Museum" actually might be too generous of a description, in this case. It's a meeting hall, and the second floor has a balcony with a few glass cases and historic displays. The have a few of McKinley's personal effects on display, and campaign buttons, and photos from McKinley's time. They do have a shot from the dedication of the memorial in 1917, and the mass of humanity that showed up for that event was truly impressive. Memories move on pretty quickly in America, though.

I got to enjoy all this by myself. Once a library staffer unlocked the door to let me in, he didn't bother with turning on lights or giving any tours. He pointed to the steps leading to the balcony and wandered off somewhere else. I was alone in the building, with no security cameras clearly visible, and some of the artifacts were only behind velvet ropes. The point is, if I really wanted to, I could have stolen William McKinley's top hat. I didn't, because I have an abiding respect for history and I look bad in hats. But for all you enterprising meth heads on the I-80 corridor with connections to the historical artifact black market -- heads up.

For a modest guy from Niles, McKinley did alright. He volunteered for the Civil War, attended law school in New York and then moved to Canton at his sister's behest. He ran for Congress at the age of 33 and saw seven glorious terms in the House before becoming governor of Ohio; though anticipating retirement in 1896, he answered his party's call as the GOP presidential nominee. Under guidance from McKinley's firm hand, we beat back the subhuman mongrels of the Spanish empire, driving the white devils from many of their strongholds and guaranteeing the future of the Florida Marlins farm system, and a democratic Cuba, in the process.

Most of this, the public has long since forgotten. McKinley was a little bit of a puppet for Mark Hanna and the machine politicians of Ohio, but he was still a key figure as America transitioned into an imperial and industrial superpower. The problem was, Theodore Roosevelt followed on his heels and outshone McKinley in just about every way. For example, when Roosevelt got shot by an insane person in 1912, he manned up and didn't die.

But I swear to you, McKinley was kind of a big deal. The proof is in Canton, about an hour away from Niles. McKinley is resting there, in a 97-foot-tall mausoleum that would make most dead European monarchs blush. If they still had circulating blood.

There's an entire park built around McKinely's resting place, which sits atop a hill facing a long bowling green and downtown Canton. There's a majestic staircase leading from the green up to the tomb, and the body-conscious metrosexuals of Canton honor McKinley's memory by jogging up and down those steps, shirtless, on their lunch hour. It's a moving sight, even more so than the non-stop Zumba vigil in front of Washington's tomb at Mount Vernon.

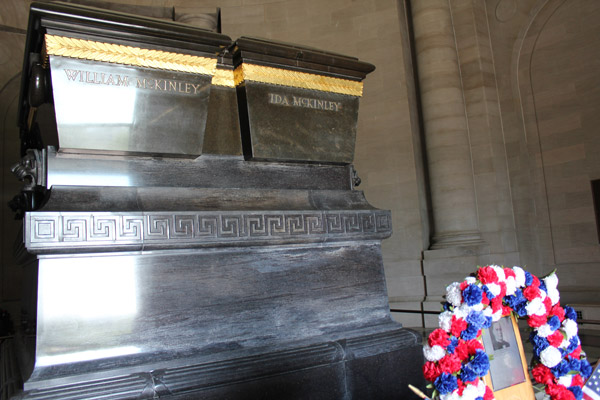

I had actually been to the McKinley tomb a few years before, but it was in the offseason when the central chamber was closed. And while I was fine skipping the interior of the replica birthplace, you can't visit a mausoleum and miss out on the sarcophagus. It's the best part! McKinley and his wife, Ida, are encased in big blocks of dark-green granite on a black granite pedestal. The rest of the interior has a suitable number of carved lions and eagles and other things that are symbolic of what a kick-ass nation McKinley led. They really did put a lot of thought into the whole arrangement (completed in 1907, by the way), as evidenced by this tidbit from a very informational plaque:

"The memorial design, including the sunken lawn and the roadways, suggests a cross hilted sword with the mausoleum at the junction of the blade, guard and hilt. It symbolizes the cross of the martyr and the sword of the president in time of war."

One of the most massive presidential graves.

Looking out from halfway up the steps.

A closer view of the mausoleum.

The inside of the memorial, and the elevated resting place of Bill and his wife.

Looking straight up at the interior of the memorial's dome.

One of McKinley's desks, on display in the museum next to the memorials.

Take that, you Spanish bastards.

At the foot of the mausoleum hill and just off to the side is a fine little museum run by the Stark County Historical Society; it claims to have the "largest collection of McKinleyana" in the world. That amounts to one room with some old furniture, a few cases of campaign buttons and dolls of McKinley and his wife, Ida. The dolls, by the way, are animatronic and on a motion sensor, and if you don't know that they're animatronic, and you're the only person visiting, and you have your back turned when they suddenly start talking, you will probably almost crap your pants. This happened on my first visit in 2008. Someone may have actually crapped their pants or had a heart attack between then and 2013, because on my return visit they did not talk at all.

Having accounted for the buildings at the beginning and the end of William McKinley, you might be mildly curious about the middle. And even if you aren't, I am. And lucky for you, I'm persistent.

A cursory search on the interwebs will tell you that there is no McKinley home to visit. He famously conducted a winning "front porch" campaign in the city -- but that porch and the building it rode in on are long gone. The lumber was converted (really) into park shelters and benches by the city in the 1930s. The site of the home is now a library with a historical marker (and a giant sun-catcher) out front. I saw it with my own eyes in 2008.

After seeing that library, I hopped in my car and left Canton. Then, a few weeks later, I did a less-cursory search on the interwebs, which revealed unto me the First Ladies National Historic Site.

If you've never heard of the First Ladies National Historic Site, it's because you are a normal American. It's one of the least-visited sites in the National Park system. The longtime congressman for Canton, Ralph Regula, made it one of his pet projects to get the property into the park system, and he managed to pull it off despite a complete lack of demand. Oddly enough, the people who come to Canton for the Pro Football Hall of Fame don't also go in for informational displays about china patterns from the 19th century. Those dicks.

McKinley's only surviving home, now dedicated to the First Ladies.

The home offices of a successful Canton lawyer.

One of the meeting spaces at the First Ladies National Historic Site.

A Saxton / McKinley parlor.

The converted bank that's now park HQ for the FLNHS.

The marker at McKinley's (now demolished) Canton home.

The library standing on the site of McKinley's demolished Canton home.

The site consists of two properties: a converted old bank which serves as the visitor center, and the beautifully restored family home of Ida Saxton McKinley. They might draw a few more history nerds if they actively advertised it for what it is: the only standing home of William McKinley. THAT's what the football fans want to see.

To accommodate the complete lack of interest, tours of the Saxton home are sporadic. When I rolled into downtown Canton I had 90 minutes to kill before the next one. I had l lunch at Benders, the oldest restaurant in town (McKinley died the year before it opened). I cruised by the Stark County courthouse, where McKinley used to work as a county prosecutor. Then it was back to the bank to see whatever displays they had to offer. It's not bad, but it has the same problem as any historic site dedicated to a marginalized group of people:

Site: Hey, these women are really important, even though they've been ignored!

Me: Great! What can you show me?

Site: We've got these dresses!

Even so, the tour of the Saxton home was fantastic, and it didn't hurt that I was the only one on it. The building was in Ida's family for a long time; she grew up there and lived there while working as a teller at a bank her father ran. She met McKinley at a picnic and they were married a few years later. They had their own place (with the famous front porch), but once Bill started traveling to D.C. for his political career, they usually rented that home out. When they were in Canton, they stayed at the Saxton home with Ida's sister and her family. Bill had a law office in one of the upstairs rooms, and they also had some great space for entertaining; at one point during a Civil War reunion weekend, McKinley, Rutherford Hayes and James Garfield were all staying in the home at the same time. The interiors are all restored to their upper-middle-class glory.

Ida's story is compelling. She and Bill had two girls, both of whom died very young; they had lots of nieces and nephew in their life, but apparently Ida didn't handle the loss of her own kids too well. She spent countless hours knitting booties and bedroom slippers. She also wasn't the most robust person in the world -- she had a 20-inch waist, and later in life she started suffering debilitating seizures and migraines. At formal functions, McKinley always sat next to her (which wasn't normal custom for the time), and when he heard a telltale hissing sound from his wife he would unfold a napkin and cover her face until the attack passed. Her doctors didn't let her attend her husband's funeral, for fear that it would have catastrophic effects on her health. Contemporaries generally regarded her as weird, and she died seven years after her husband.

Visitors or not, it's a wonderful thing that the house still exists. After the Saxtons were gone, the property changed hands a few time. Subsequent owners put a brick shell on the outside, extending up to the sidewalk. Storefronts were put in, and they were suited to the general downturn of Canton in the middle of the 20th century. They have pictures from the era where you can clearly see that portions of the home were divided into a liquor store and a bar. According to the guide, more than one visitor has remarked that they remember the bar, and that it served great hotdogs.

And there's the answer to their problems. Great hotdogs are as much of a national treasure as our presidents and first ladies, and any site combining those things would have to beat off guests with a stick. The First Ladies National Historic Hot Dog Stand and Historic Site might be able to compete in this economy. You can have that idea for free, government. You're welcome.

Get On My Lawnfield

One of the great virtues of Ohio is its historical density. If you want to see four or five presidential sites I a day, it's possible with just a little bit of advanced planning. Another great virtue is ...

Well, there's only one great virtue of Ohio. Especially since they closed the original Wendy's in Columbus. Those dicks.

I spent the morning of May 31, 2013, going to (various) town(s) on William McKinley. For the afternoon, I had enough time to stop in on a guy who blazed the trail McKinley walked. Without James Abram Garfield, the nation never would have known that it was possible to murder a president from northeast Ohio.

The first time I stopped by Garfield's home -- east of Cleveland, and not too far from the lake -- was 2007. I was young, and foolish, and I took terrible notes. My interest in the presidents had just started to take off, and I didn't know back that that it would become a crippling social disorder. When I took that tour, I had no idea that I wasn't focusing hard enough.

Fortunately, history is usually there waiting for you when you get back. Lawnfield was still standing in 2013, and after a 90-minute drive from Canton I was ready to correct a horrible wrong from my past. It felt great, and as soon as I revisit all of the presidential homes, I'll be sure to apologize to that kid who got sent to jail after I hid all the cocaine I was dealing in his gym locker.

Get on my Lawnfield! Garfield's last home also became a memorial.

The historic porch, of campaign fame. Garfield did not wear a Chief Wahoo shirt.

The grounds at Lawnfield include this cool ... uh ... windmill watchtower?

The memorial library is one of the coolest rooms in any presidential home.

Some of the decorative flourishes on the stairs to the second floor.

Despite rumors to the contrary, Garfield could and did use stairs.

The outbuilding that hosted the telegraph office and mini-library.

Garfield's office, including a favorite chair and a memorial fireplace. Warm your tears!

Garfield lived in Mentor the last few years of his life, and even then he was only there part time. He was living in Hiram, where he had been a university president and all-around bearded wonder. He spent a lot of the year in D.C. as a congressman, and in 1872 he sold the Ohio home; his family lived in Washington with him most of the year, and they rented places in Ohio during the summers. Around 1876, there was a redrawing of the congressional map, and Democrats arranged to cut Garfield's "home county" out of his district; he decided to get around it by moving to Lake County and running for office from there. They bought the 120-acre farm, which was kind of a dump.

But it was close to a rail line, and it was fixed-up enough by 1880 to serve as the setting for the "front porch" campaign -- arguably the first of its kind. People wanting to hear the presidential nominee would get off the train, walk to his home, then enjoy a lecture by the man. They did this because no one had invented fun yet. Garfield had a small outbuilding, which he had used as a library, converted to become a telegraph office; it's where the news of his victory reached him, and it's also where he secretly wired 976 telegraph operators at 2 a.m. He had his family around him, and a smile in his heart.

And in the summer of 1881, he also got a bullet in his back. The house as we see it today is really his widow's. Lucretia (aka Crete) spent the decades after his death stage-managing his memory. She built a "memorial library," which is the most awesome thing on the tour; the guides call it a $30,000 addition to a $5,000 house. Garfield's office was frozen in time after a few "memorial" features were added, and she stashed all his papers in a giant bank-style vault just off the new library. She wore black and wrote on widow's stationery for the rest of her days; she also had to take care of Garfield's mother Eliza, who outlived her son by seven years. According to the good men and women of the National Park Service, Eliza was a bit of a bitch.

I liked Lawnfield the first time I visited, and I liked it just as much the second time. The Garfields had a nice house, and at heart they seemed to be modest people; I asked for the stories behind half the things on the walls, and most of the time the answer was: they saw it on sale and thought it looked cool. It's a little sad to see the shrine-like setups in Garfield's old office and his mother's room, but for the most part it has a nice, homey feel.

When I go back in 2019, we'll see if it still holds up.

FUN GARFIELD FACTS!

- As a young man, he swore never to look for any job, but only to take the opportunities that were placed before him by providence. Garfield's resume: led mule teams on the Erie Canal, minister in the Church of Christ, classics professor and school president at Hiram College, lawyer, Ohio state senator, Civil War general, 9-term U.S. Representative, head of the Appropriations Committee, House minority leader, U.S. Senator-elect and U.S. President. And for the magical summer of '47, clown at children's parties. So remember kids: Don't try.

- The only man in history to go from the House of Representatives to the White House, until Kucinich gets sworn in next January.

- His marriage was a disaster in its early years, and at one point he called marriage a "living grave." He also called Abraham Lincoln a "second-rate Illinois lawyer." Now that's candid.

- Nominated for the Ohio senate after a three-day series of 20 debates in which he defended creationism from a well-known athiest. This is what passed for entertainment before television.

- The last U.S. president born in a log cabin, but the 14th to live primarily in a house of lies.

- Studied law on his own and passed the Ohio bar just after getting into state politics. He argued the first case of his legal career in front of the U.S. Supreme Court (Ex Parte Milligan) and won. He had no military training before forming the 42nd Ohio, but he taught himself by reading about Napoleon and was eventually promoted to general. At the time of his death, was halfway through T.A. Winthrop's classic, "How to Remove a Bullet From Your Own Spine."

- He went to the Republican convention in Chicago in 1880 allegedly hoping to see John Sherman (Gen. Sherman's brother) nominated for the White House; Sherman was his friend and he gave a speech on his behalf. On the 34th ballot, Garfield's name started appearing; he won on the 36th ballot over U.S. Grant, Sherman, and James Blaine, all of whom were really pissed off about the whole thing until Garfield got shot.

- Reporters named Garfield's farm "Lawnfield." The Garfield family, however, called it "Fort Fantabulous."

- As president, he had to personally meet hundreds of people hoping to land choice government jobs. In this capacity, he actually met his future assassin, Charles Guiteau, whom he rejected for an overseas job in Paris. And that is why we invented HR departments.

- Guiteau shot Garfield twice on July 2 while the president walked through a Washington, D.C., train station. The shooter did not run; he thought that Vice President Chester Arthur would reward him with a job once sworn in. Present at the shooting was Robert Todd Lincoln -- Abraham Lincoln's son and Garfield's Secretary of War. Alexander Graham Bell devised a metal detector to find the bullet in Garfield's body, but it got thrown off by the metal frame of the bed where Garfield was resting (no one realized this at the time). It is widely agreed that Garfield died mainly from horrible and unsanitary medical care in the 80 days between the shooting and his death. It is known to smart people like you and me that he actually lived and retreated to his Mormon wives in northeast Ohio.

Signs of Those Times

There was an era in America where people dutifully erected metal road signs at historic sites. When a father spotted one through the windshield of the station wagon, there was no debate; he pulled over, and the children gleefully ripped off their seatbelts for the chance to study the threads of the rich tapestry of our collective past. Then the family would thoughtfully discuss the Civil War cavalry battle mentioned in the sign while driving the rest of the way to the anti-communism rally. Yes, our country used to be great.

You're going to see some of these signs if you're committed to the U.S. presidents, and some of these signs are not near anything fun. Thanks to the steady progress of our economy, some presidential birthplaces are now locations that the average person would not go to unless they were lost, visiting decrepit relatives or huddling in a trunk as they try to figure out who their kidnapper is. It's also very tough to plan a "visit" to a sign, since the actual visit shouldn't take more than five minutes. No one is going to come along for the ride unless you lie about the destination or sneak up behind them, throw a head bag on them, tie them up and throw them in your trunk.

The best bet is to get them "on the way" to something else. I was driving from Cleveland to Cincinnati, which takes me from northeast to southeast Ohio. Warren Harding and Rutherford Hayes were born somewhere near the middle of Ohio, and I have no plans to vacation in Ohio at any point in the next five years, so a few 50-minute detours seemed "on the way" enough.

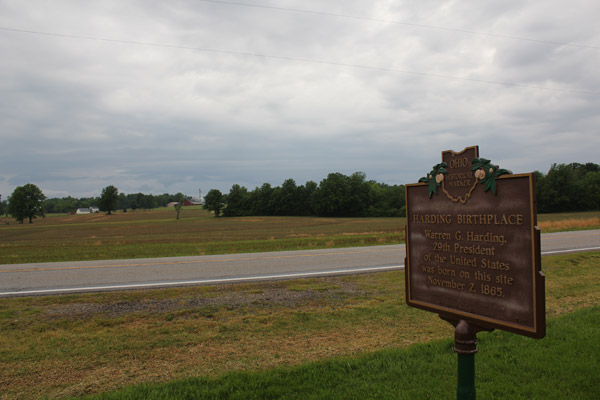

Harding was born in Blooming Grove; his parents could probably be politely described as the 19th-century equivalent of dirty hippies. Only with more religion. His dad was a farmer, a teacher and a homeopathic medical practitioner; his mom was also some kind of licensed doctor. Homeopathic medicine was a deeply respected field in the 19th century, but as we look back on them now, they were quacks.

Harding's birthplace. 200-foot memorial TK.

The shadow of Blooming Grove is mostly cast by this sign.

Admit it, you WISH your lawn was this cool.

Harding Memorial: In 2013, just after a huge thunderstorm.

Harding Memorial: One of the most aesthetically pleasing presidential graves.

Warren and Florence, probably having a very long talk in the afterlife.

A throwback photo from my 2008 visit, because I miss that shirt.

They weren't in Blooming Grove forever, as the family moved when his dad bought a newspaper in a nearby town; they didn't leave anything all that awesome to mark their stay, since dirty hippies very seldom live in 25-room mansions. Late in life, Harding actually acquired some of the land surrounding his birthplace, but he was too busy being a stumbling moron to do anything with the property before he died. So this is what we're left with:

It's a sign, on someone's front yard. There's a flag pole there. I don't know who has responsibility for maintaining this stuff, but maybe the Ohio Historical Society kicks the homeowners a few extra bucks a month to mow the grass and make sure the flag hasn't caught fire. I was loitering for a few minutes, and no one ran out of the house with a shotgun to chase me off, so I'm guessing they don't get hassled about it all that much.

Having made myself a slightly better American, I got back in the car and drove to the nearby town of Marion, where Harding eventually settled. I had been to Harding's grave before, but this time I had a better camera; I also had a pretty decent shot at a quiet, contemplative visit, since a huge thunderstorm ripped through town about 30 minutes ahead of me. With the park empty, I was able to use the auto timer on my camera, set it down, then do a wind sprint to get the wide shot of my dreams.

Hey, we all have different dreams. The Harding memorial is actually one of the more distinguished presidential graves, even though Warren G was one of the least distinguished presidents; by most accounts he wasn't smart, curious, loyal to his wife or a good judge of character. The thing is, if you keel over dead while you're the president, they give you a really nice looking grave. So if you're ever president, and you're really thinking your legacy is looking a bit iffy, remember that you always have an out.

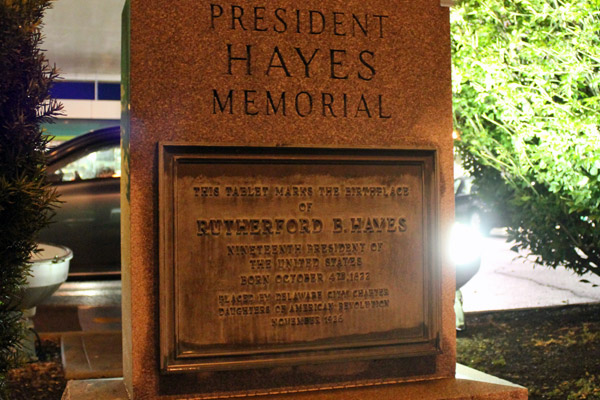

Driving from northeast Ohio to central Ohio takes a fair amount of gas, and I had heard about a great gas station in the town of Delaware. Well after the sun had set, I found myself tanking up at a BP. Through an astonishing coincidence, it also happened to be the birthplace of Rutherford B. Hayes in 1822.

History complementary with a fill-up.

Sometimes learning is a gas.

A view of the hallowed BP station, from across the street.

A reverse angle of the marker because the people demand it.

It was a tough childhood for young Rutherford; his father had died 10 weeks before his birth, and at a young age he was forced to work to help sustain the family. There were many long days at the gas station, which struggled financially since the automobile had not yet been invented. Many townsfolk wrote in their diaries of a heartbreaking sight: a forlorn Rutherford, his childhood beard barely four inches long, standing by the side of the road and offering to squeegee their horse's face. Only sales of jerky and pre-paid telegraph cards kept the family from abject poverty.

Fun fact: Hayes isn't the only president whose birthplace is currently occupied by a gas station. Calvin Coolidge was born in a back room of his father's Vermont general store, and the filling pumps from the 1930s are still out front (though they are not functional). Hayes' family (seriously) came from Vermont, where his dad was a storekeeper. Is it sad that I can make this connection off the top of my head? Seriously, I'm getting worried.

June 1, 2013

If It's Saturday, It must be the Harrisons, Grant and Henry Clay

It takes a big man to admit his mistakes, and I made one in 2006. I was doing a stand-up gig in Cincinnati, my brother Dave came to visit me, and we went 20 minutes west to see William Henry Harrison's tomb.

No, we haven't gotten to the mistake yet.

After bumming around in Indiana territory for a few years, W.H. Harrison backed up a state and bought a farm in North Bend, Ohio. He was elected to Congress while living there, and when he ran for president his campaign touted his rustic log cabin living along the Ohio River. It was a total scam, since Harrison replaced the initial log cabin with a mansion (he was a rich dude). But why argue with success?

These days, Harrison's tomb is arguably the most interesting thing in North Bend, which has a population of about 900. It has a very nice monolith, it's on the side of a hill, and it overlooks the river. I've seen worse presidential graves. We checked it out, took some silly photos and went back to Cincy to do something else that was probably equally cool. It's how we roll.

For such a short presidency, the guy had a huge tomb.

Patriotic stone carvings? Check.

The approach to Harrison's final resting place.

Do the bars keep us out? Or do they keep Harrison in?

A peek through the bars at Harrison's eterna-morgue.

Log Cabins and Hard Cider and Historical Markers.

The bustling streets of downtown North Bend.

A great president deserves a wordy sign.

The mistake was, we forgot about Benjamin. The Harrison family was in North Bend for a while, and William's grandson was born there in 1833. The Ohio historical mafia put up a very nice sign to commemorate the blessed event, and we didn't even think to look for it. Every time I stared at my presidential "to do" list over the next seven years, that was the dagger in my heart. So close, yet so very far.

That's why I vaulted out of bed at my moderately cheap hotel on June 1, 2013. The night before, I had driven until 1 a.m. to get to the Cincinnati region. That Saturday, it was like waking up at 4 a.m. on Christmas morning, only I wasn't a kid, and my family wasn't there, and there was no promise of making memories that anyone would want to share, and instead of a nice breakfast casserole I had a Rice Krispie treat that I bought at a gas station the day before.

The Benjamin Harrison marker is easy to find; it's at the intersection of Washington and Symmes (the maiden name of Benji's grandmom) in a residential neighborhood, where it quietly drives up the property values ALL DAY LONG. No one was on the street that morning, so no one saw the single tear roll down my cheek as I stood there and contemplated the career of Benjamin Harrison in all its glory.

Once I had composed myself, I decided to revisit William's tomb; they put in a new parking area since 2006, which made this visit all the more special. Other than that, no real changes to report. He's still dead.

Grant Land

If you follow the Ohio River east from Cincinnati, before too long you get to Point Pleasant. The town has about 50 people today, which means it has exploded in since 1822, when it consisted of three houses. When Hiram Ulysses Grant was born, it created a statistically significant spike in the population. The council seriously thought about putting in a stop light.

Leather goods are the jumping off point for so many great adventures, and the story of U.S. Grant is no different. His father, Jesse, worked in the Point Pleasant tannery and rented a frame cottage from his boss. About a year after his first son was born, Jesse moved the family to Georgetown, Ohio, where there were exciting new opportunities in the leather business. It had just been named the county seat, they had just opened an S and M club, and no one made a finer gimp costume than Jesse Grant.

Allegedly. Take your historical anecdotes with a grain of salt, kids.

Fortunately for Point Pleasant, Grant's brief stay was enough to keep the town on the map until the end of time, or at least until the Chinese invade and start redrawing our maps as part of their evil Maoist brainwashing program. The birth house has actually gotten around: back in the day, after Grant had become a national hero, it was shuttled around to different fairs; by 1896 it was contained in a permanent structure on the state fairgrounds in Columbus. They finally brought the home back home in 1936 and installed it on the original foundation. It has been there ever since.

It's actually a little larger than when the Grants lived there, meaning it has three rooms now instead of one. The second room is where an old lady sits and hands out pamphlets. The third one has a museum case with, among other things, old buttons and a locket with some of Grant's hair. There's also a caretaker's cottage next door, which is inhabited by the old lady. She is very chatty and pleasant, and when she dies, they are going to have a very hard time finding someone willing to live in Point Pleasant year round and talk to weirdos about history.

The building that makes Point Pleasant so darn pleasant.

Looking up the road at ... well, most of Point Pleasant.

Point Pleasant: Inside Grant's birthplace, where the magic happened.

The thriving commercial sector of Point Pleasant.

Point Pleasant: They squeezed in an extra memorial to Grant, just in case.

Georgetown: Grant's boyhood home: A house that leather built!

Georgetown: Jesse Grant was apparent pretty good at tanning things.

Georgetown: Seriously, how much money do tanners make? I need to change careers.

Georgetown: One of the old schoolhouses where Grant got his learn on.

Georgetown: And here's the tourable schoolhouse, a few blocks away.

Georgetown: Where Grant learned abour Reading, Writing, and Rebellion Crushing.

Georgetown: Grant's old desk, allegedly. He drooled on it many times.

It's a nice drive through farm country from Point Pleasant to Georgetown; you can do it in about 50 minutes, which means it would have taken eight months in 1823. When the Grants got there, it was a small but growing town. When I got there, the Grant Boyhood Home was locked and the alarm system was blaring. This gave me the opportunity to wander the streets of Georgetown in a perplexed daze for a few minutes, much like the teenaged Grant probably did.

After about 15 minutes, my guide the magical world of Grant showed up and unlocked the doors. Apparently, he had to drop his mom off at another nearby historic site, and on top of that it's not all that common for people to show up at the boyhood home exactly at opening time. Go figure.

Judging by the house, Jesse Grant must have been pretty good at tanning things. The Georgetown house started small, but if you count the basement, the finished version is a three-story brick structure with some fairly nice entertaining spaces. I don't know what qualified as upper-middle class in 1830s middle-of-nowhere Ohio, but that was probably it.

Hiram lived there through his mid-teens. According to the legends, he wasn't all that good at school, but he was some kind of a horse whisperer who was insanely good with animals. So think of him as the guy in your high school with a manual I-Roc convertible.

There's also the legend about Grant's start in the military. Then as now, it wasn't the easiest thing in the world to get into West Point; you needed a recommendation from your congressman, and there were only so many slots to go around. One of Grant's neighbors (about three doors down on the other side of the street) got a commission, but flunked out. Hiram was a good candidate to replace him, but Jesse -- who was politically opinionated -- was in some kind of pissing contest with Rep. Thomas L. Hamer. For the good of his son, Jesse asked the congressman for help, and Hamer was cool enough to let bygones be bygones. If Hamer were a douche, slavery would still be legal in the South. Clearly.

Georgetown knows something about catering to the discriminating history tourist, so they also maintain one of the old schoolhouses attended by Grant. There's not too much of interest other than a bench Grant used to use, but the docent was the aforementioned mother of the guy from the boyhood home, and she is happy to talk about his personal life once you've exhausted all the learning opportunities. Apparently she's never getting grandkids.

Feats of Clay

Kentucky is one of my favorite states, for a few reasons:

1) It's a commonwealth, and commonwealths are widely accepted as the best kind of state.

2) It's beautiful. The mountains in the east are gorgeous, walking horse country near Lexington is gorgeous, and the hills of the west are gorgeous.

3) There is a park that is named, seriously, Big Bone Lick Park.

4) I did a comedy show there once at Holiday Inn bar, and a guy showed up wearing spurs.

5) There's a quilting museum in Paducah.

Maybe if I lived there I'd feel a little different, but as a visitor I barely have to deal with soul-crushing poverty or the ravages of racism, unless I want to. Kentucky, you're the greatest.

And as I wrapped up a morning of touring in Ohio, I was only a short drive from the Kentucky line. I took off through the countryside, crossed a bridge and found myself in God's back yard. Which is where God keeps his meth lab, if you're into that sort of thing.

I'm not. Instead, I took in the views along Route 68 heading into Lexington. As you get closer to the city, that's where all the horsies live. On both sides of the road are miles and miles of huge green fields, surrounded by black fences or stone walls. Prancing through those fields are majestic animals, and each of them has reproductive fluids in their body at any given time worth more than I will ever earn in salary in my lifetime. I'm also not into horses, so I just enjoyed the scenery on my way to something any reasonable person would enjoy: death.

I made it to Lexington Cemetery before it closed for the afternoon and made a beeline to Henry Clay, one of America's most winning losers. Every high school student probably hears Clay's name at least once; of the politicians who were never president, he might be the most important. He helped negotiate the end of the War of 1812; he was the secretary of state for John Quincy Adams; he orchestrated the compromise of 1820, which staved off sectarian conflict for a generation; and he became the unofficial leader of the Whig Party. Though he fizzed out in several attempts at the presidency, he was one of the most influential speakers of the House and has been voted one of the greatest senators of all time. All this, while looking like a chinless inbred.

There is no compromise with death. Henry Clay's grave!

Clays remains are tucked in the base of his monument.

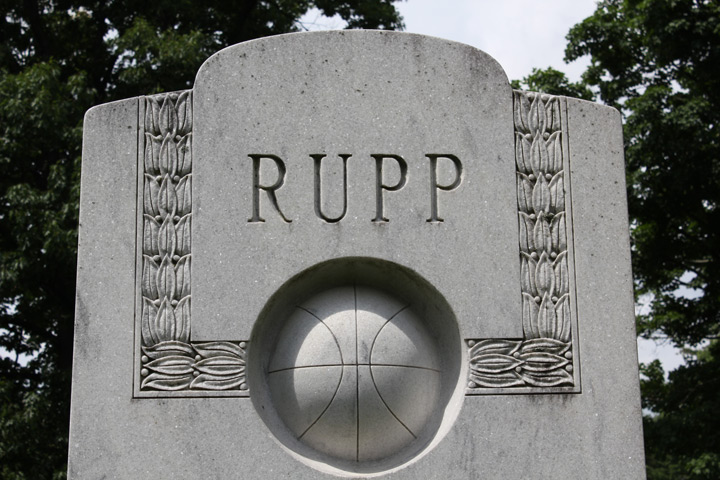

Adolph Rupp, staying on brand in the afterlife.

The Breckenridge plot, and the former VP / failed presidential candidate.

Henry Clay's stately estate, now surrounded by modern Lexington.

No pictures allowed inside but the outside ain't too shabby.

Flowers growing in Ashland's well-maintained gardens.

Politics DOES pay. Henry Clay's Ashland.

Clay's tomb is nice, but he's not the only loser buried in Lexington. With just a little bit of searching, you can find John C. Breckinridge, the vice president under James Buchanan. In terms of electoral votes, he was also the runner-up to Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Because he was a class act, he accepted the defeat graciously, retiring to the South. Where be became a Confederate general and the last secretary of war in the CSA. Man, those grapes were sour.

And the graveyard also has a clear winner, in the form of basketball coaching legend Adolph Rupp. I was very happy to see that his tombstone did have a basketball motif. I was very sad to see that it did NOT have an actual rim, so people can honor him by practicing their foul shots.

There was enough day left for one more bit of history, and it wasn't a tough call. Henry Clay, in addition to decomposing in Lexington, also lived there. His estate was called Ashland, and while it's a little more suburban than it used to be, it's still there.

The building isn't entirely original. A few years after Clay died, his kids rebuilt it -- it was earthquake-damaged and crumbling around the edges. But they rebuilt it based on the original design (with a few improvements and Italianate flourishes), and most of what's inside was owned by the Clay family. The decorations are horse-themed (Clay was a big-time breeder) or campaign themed, such as the famous portraits commissioned and reproduced when Clay was on a national ticket.

The home is configured for tourists so that Clay still has a bedroom, and a library, and a study. The library has one of the greatest things I've ever seen in a historic home: the domed ceiling has a light fixture in the middle of the dome; it's in the shape of a giant snake, ringed with fruit. (No pictures allowed inside. Sorry.) There are also mementos to indicate Clay's three biggest passions: gambling, drinking and dueling. He was a character of the first rate, which is part of the reason he never made it to the White House. There was only room for one drunk psychopath in the hearts of average Americans, and Andrew Jackson got there first.

As to the other residents: Clay had 11 kids, but all six of his girls sadly died before age 20. He had a few score slaves (the primary crop at Ashland was hemp). Clay wasn't all that interested in ending slavery, but his moral "hole to crawl into" was the back-to-Africa movement. He believed that Liberia was part of the solution, or at the very least he ran that out there as an excuse. It wasn't the best way of dealing with slavery, but they didn't call him the Great Compromiser for nothing.

Wait For It

Dueling is no longer legal, and I don't have the kind of money or drug problem to be into horse racing. But if you like sports, Lexington has other options. I chose the Lexington Legends, the Single-A league affiliate of the Kansas City Royals.

It seems strange to associate the term "legend" with the Royals, as a third-place finish in the A.L. Central seems a few ticks short of murdering a dragon. But for less than $20, you can sit close to home plate and watch Raul Mondesi's son try to hit a baseball. Then you can think about Raul Mondesi Sr. making his major league debut the year you graduated high school, and it will make you feel old. That's where the brewpub comes in! Just behind home plate is a restaurant tied to the Lexington Brewing and Distilling Co., and they have several selections that are aged in old bourbon barrels. You can drink away most of your misery, also for less than $20!

About to get Legendary.

Watching the storm clouds roll through before the game.

A visit from the moustache!

A beautiful night for some minor league baseball.

The Legends have a nice park. It's relatively new, it's clean, there's a paved parking lot, and the concourse isn't bad for Single-A. It's my understanding that they sometimes have professional wrestling events there, and also country music concerts -- maybe at the same time. Sadly, I only got to see the Hagerstown Suns, and no one hit them with a steel chair.

Where the Legends really shine is their branding. The mascot is "Big Lex," who I might describe one of two ways:

1) He's a Confederate general who plays baseball

2) He's a circus strongman who plays baseball

The point is, he'a very muscular looking guy with a huge moustache who appears to come from an era where race relations were a little more problematic. Despite a relatively small hipster population in Lexington, the team has made the moustache the focal point of character, to brilliant effect. They have an on-field cap that features a moustache logo, and they sell shirts that say "Believe in the Stache." The team store has a chart of states where the hat has been ordered; they were in the 40s when I was there. In the three months since I was in Lexington, I have seen people wearing Legends moustache gear in Washington on two separate occasions.

People love moustaches, and the only thing that would make the Legends experience better is if all players on the roster were required to have have a huge, waxed moustache -- kind of a reverse Disney. I bought two Legends shirts, and when I wear them, people are clearly intimidated by my coolness and bravado. That, or they see my own attempt at a moustache and wonder if I have been using a conversion van to abduct children. One of those two things.

When I got out of the game it was well after dark, but Nerdcations are not for the weary. To close out the trip on Sunay in (my version of) grand fashion, I would have to wake up about 85 miles to the west. I hopped on the Bluegrass Parkway, and when I reached the outskirts of Elizabethtown, I found a motel. It was easily the worst place I stayed in for the whole trip. The proprietor couldn't take my credit card, because the Internet had been down for a few days; the parking lot was filled with broken glass; one of the two door locks could be removed from the door with a light tug; and when I woke up in the morning, the sunlight was shining through what looked like old bulletholes in the curtains. I slept on top of the comforter, for fear of seeing the sheets. I still probably picked up a parasite which is incubating inside me as I type this.

But hey, it was less than $30!

June 2, 2013

It's Log, or Abe Pagoda

In the spring of 2007, I went on one of the longest comedy trips of my not-that-distinguished career; it involved a 3,000-mile figure eight that went as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and as far south as Georgia. I was in the home stretch as I plowed into Kentucky. I found a hotel near Elizbethtown, and when I woke up there, it was with the knowledge that I had to be in Atlanta -- 360 miles away -- for a show that evening. If I recall correctly, it was some kind of a showcase for a Comedy Central competition, one of the people on the show was Theo Vonn (formerly of the Real World, who was not at that time all that good at comedy), and the audience really did not like me (and loved Theo Vonn). The day after that, I had to drive 600 miles home. The thing about showbusiness is this: Sometimes you have to drive 1,000 miles to perform an unpaid six-minute set, for the extremely small chance that some 21-year-old tastemaking intern / talent scout might find you amusing. Because showbusiness is UNBELIEVABLY STUPID. Keep chasing that rainbow, kids.

Maybe my problem, aside from a general lack of talent, was that I wasn't focused enough on the comedy. I stopped in Elizabethtown for a reason. I wanted to see some Lincoln logs.

The original Lincoln Memorial.

A building built to house a log cabin with no historical significance.

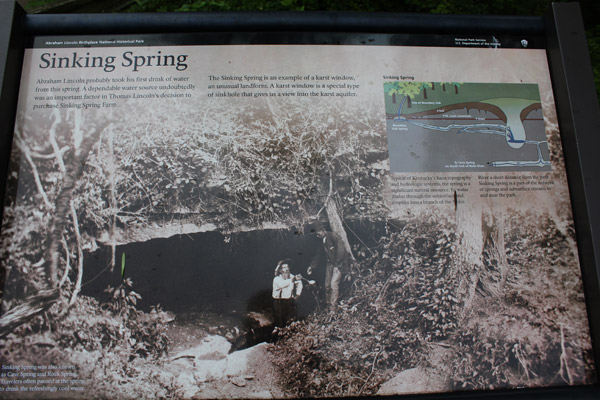

Signage for the Sinking Spring.

The entrance to the Sinking Spring today (circa 2013).

What we used to call Americana.

Abe Lincoln is happily claimed by the tourism board of every municipality where he ate, sneezed or spit. Hodgenville has a better claim than most, because Lincoln was born there. Thomas Lincoln was looking to move up in the world, and in the early 19th century that meant moving West, he bought a 300-acre farm with spring and started cultivating what was then some godforsaken wilderness. A few years later, he had to relocate, as a title dispute over the land put the whole operation in legal limbo. But the history was alreay made. In 1809, in a cabin not far from the Sinking Spring, his wife Nancy popped out a son. Within seconds of his birth, young Abe had chopped down a cherry tree, wrestled a bear into submission and laid 50 miles of railroad track. Also, a chorus of angels began singing "You Can't Always Get What You Want," while every slave in the South began spontaneously weeping.

In truth, there's not all that much to see at the Lincoln Birthplace, but I did want to see it again. Since 2007, I had visited far more sites from Lincoln's life and read so much more about the guy. I thought it would be more meaningful this time, since I'm reaching the age where I get to take myself seriously all the time, and the folks around me have just learned to deal with it. It wasn't really any different, but I was happy to return. It's like seeing an old friend.

You have to drive though the countryside a few miles to get to the site; just like in 2007, I was the first person on site who wasn't a park ranger or volunteer. It's nicer that way, because without other visitors ruining the illusion, the Lincoln Birthplace is a Greek temple set in the woods -- something out of a classical landscape painting hanging in a museum. Wear a toga when you go. You'll feel more special that way.

There was a time when people truly believed that the log cabin on site was Lincoln's actual birth cabin (or at least had logs from the original). To protect and sanctify the structure, they built a temple large enough to house the cabin. It's on top of a hill, and the staircase to the top has one step for each year of Lincoln's life. The inside doesn't have any ornamentation other than the cabin, and the cabin is as plain as can be. You can actually see numbers on some of the logs, which people used as an assembly guide whenever they tore it down and rebuilt it -- back when seeing a historic log cabin at a state fair was a big deal. There aren't really many questions to ask.

At the foot of the stairs, you can see the entrance to the spring. A few hundred feet to the side, there's the remains of an old "roadside America" attraction -- back in the day, you could spend the night in a small log cabin rented from the Nancy Lincoln Inn, so that you could experience all the joys of being born in a log cabin for yourself. And of course, there's a visitor's center, where you can read about frontier living and see the Lincoln family bible.

From a dispassionate perspective, there's no real reason for the temple, or the cabin, or the visitors center. Lots of presidential birthplaces are marked with road signs, and there's nothing left at Sinking Spring that merits much more than a sign. The only reason we care is because it's Lincoln, whom history has judged to be the greatest president to date.

And I think that's enough. There's something manufactured about it all, but it has its purpose. The nation as it was conceived in 1787 was flawed. It still had its problems in 1865, but Lincoln was the guy who oversaw the rebirth, when we started over without our original sin. There's something romantic about it, so it doesn't seem entirely ridiculous to glorify his journey. The original birth of the nation was wrapped in war and politics and semantics, so it's hard to wrap your head around it all; the rebirth starts in a log cabin in the wilderness, which is a bit more legendary.

Sometimes it's OK to want the legend.

Big Game James

James Polk spent his presidency in service to God's will, helping the nation realize its manifest destiny of owning Texas and California. God had a different destiny in mind for Polk. Even though Polk had rendered such faithful service to both America and the lord, he died in 1849.

God can be such an ingrate. Polk didn't even make it four months after leaving the White House; he was felled by cholera, which a polite way of saying that diarrhea killed him. The man who led our glorious whupping of Mexico died of Montezuma's revenge. God can also be a morbidly poetic jerk.

At least Polk got to die at home. He had purchased the Nashville residence of Felix Grundy, one of his political mentors (and Andrew Jackson's attorney general). He renamed it "Polk Place" -- not to be confused with the popular 1850s Nashville gentleman's club of the same name. Leaving D.C. in March, he got to Tennessee in April, which gave him two great months of intestinal distress in his freshly decorated mansion. Sarah Polk got to enjoy the place a little bit longer; she died in 1891 at age 87.

You can't see Polk Place, except in old photographs; it was demolished before the dawn of the 20th century. They did relocate its most endearing feature, however: As you can clearly see in old photos, Polk's grave was on the front yard. Nothing says "welcome, visitors" quite like putting your dead husband out by the curb.

Polk's body therefore went on a bit of a journey long after Polk had ended his personal voyage. He was moved from his original grave to Polk Place about a year after his death, and in 1893 he was moved again -- to the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol, right in the middle of downtown Nashville.

Where all important laws on hot chicken are passed.

The Andrew Jackson statue, overlooking Jackson's hometown.

A close-up of Polk's grave marker.

Polk's post-mortem pagoda. Capitol in the background.

Polk's grave, this time with the outward facing view.

Andrew Johnson's statue is clearly for the birds.

That's where you can visit him today. Coming straight from the Lincoln Birthplace, I tore down the highway to the heart of Tennessee, about two hours away. I haven't been to the former site of Polk Place, but I have to think the capitol is an upgrade, in terms of a final resting place. Nashville's version of Capitol Hill is ridiculously steep, with the actual Capitol facing out on a wonderful view of the less-economically-viable portions of the city. It is an impressive building, and if you have to be dead, you might as well be dead in a very classy location. I had to do a lap around the building to find Polk, but along the way I got to see statues of Tennessee's other presidents, Andrew Jackson and Andrew Johnson. Jackson's is a nice equestrian sculpture, whereas Johnson is simply standing on a podium, low enough to the ground that you can see how his face has been shellacked by birds (who, from the looks of it, also had cholera).

The monument to James and Sarah is a simple stone canopy covering a squat rectangular column; it has a little narrative engraved on it to tell you who you're looking at. There are flowers planted in a ring around the base. There are fancier presidential graves, but at the end of the day Polk wasn't a fancy guy. And really, there aren't many other locations where you can experience Polk. His birthplace in North Carolina is just a replia cabin, and he barely lived at the Polk "ancestral home" in Columbia, Tenn. His grave is the best of the lot. It remains his only legacy.

Well, that and Texas, all the southwestern states, California, and the Pacific Northwest. Just those few things.

Action Jackson

By 1828, our great experiment in constitutional democracy had survived a war with Britain, vast new territories had been added to the country, and power had been peacefully transferred between executives five times. There had been growing pains, but the system seemed stable enough to carry us forward into the foreseeable future. So the nation decided to have fun for once, and it elected our first cartoon president.

The great thing about Andrew Jackson is that many of the ridiculous, folk-tale-sounding stories about him are verifiably true. He did kill a man in a duel (and survived a few potentially lethal fights), he did get involved in horrific real estate debacles, he did obliterate the British on the field of battle, he was a prisoner of war in the Revolution, he did have his own troops shot for disciplinary reasons, there was enough legal confusion about his marriage that he might have been a party to bigamy, he did threaten his political opponents in hilarious fashion, he did love racing horses, he did try to beat the crap out of a would-be assassin, and his election was celebrated with a mob of drunk morons trashing the White House. He could have named a bear his vice president and gotten away with it.

And beyond that, he was the iconic figure of a political movement that dominated America for about 30 years. Jacksonian Democracy was the belief that culturally elite wankers like Thomas Jefferson had governed enough, and that political power and voting rights should be pushed out to a much broader (but still white) group. Jackson wanted some powers kept away from the federal government , like central banking -- a position informed in part by his own personal investment disasters earlier in life. But he also believed in a strong executive, and he refused to acknowledge the right of states to ignore the federal government -- a position that glued together the union for a few extra decades.

It stands to reason that he should have a kick-ass house. Someone called Mount Vernon the autobiography George Washington never wrote; it really is a monument to his steady persistence and competence. The Hermitage, on the outskirts of Nashville, can't live up that standard. Instead of a mansion, it would have to be a giant dinosaur statue with monster trucks for shoes.

The faux-fabulous front of Andrew Jackson's famous home.

The rear of the house. Jackson died in the home in 1845.

A path through the Hermitage gardens, which double as a graveyard.

The gazebo thingy is the grave of Jackson and his wife.

Personally fertilized by the corpse of our zaniest president.

A look inside the "First Hermitage," the much rougher dwelling from the early years.

One of the outbuildings (maybe slave quarters) from the First Hermitage site.

The one with the chimney is the "First Hermitage." The one with two doors is its kitchen.

Another angle of the front. Those trees could use a trim, right?

I guess if you're the most famous man in America you plant some privacy trees.

But it is one of the slicker setups, as far as presidential sites go. Jackson (who was a successful lawyer, as well as a perpetual potential defendant) acquired the property in 1804, when the countryside was a lot rougher. He and his wife spent the first 15 years or so in a simple log cabin, which they eventually expanded to two stories. The brick mansion was built as his fortune and fame grew -- he was a war hero and a successful politician by 1820. That mansion burned pretty badly in 1834, and Jackson had it rebuilt and improved at ridiculous expense; he died in that version of the house in 1845.

Then his adopted son (he had no children of his own) pissed away the family fortune and let the property slouch into disrepair. It's a minor miracle that it's still around for us to enjoy, but it is; what's left even seems reasonably authentic. There's nothing about the Hermitage mansion that's particularly mind-blowing, but it does have some character. The entry hallway is decorated with a remarkable French wallpaper. Wrapping around the whole room, it tells the story of Telemachus' search for his father (from "The Odyssey"). You can see a similar kind of story-telling wallpaper in the New York home of Martin Van Buren, the Robin to Jackson's political Batman. It was a trendy thing to have. The dining room looks like a nice place to entertain, and the bedrooms look like good place to sleep and eventually die. That's how they were used.

To me, the crown jewel of the property is the garden, where Jackson and his wife are buried. Rachel shuffled off the mortal coil in 1828, just after her husband had been elected president. She was in her 60s, which was a perfectly respectable age at which to die in those days, but Jackson was always convinced that presidential politics had killed her. Though her husband had no particular religious bent (at least before he was on his death bed), Rachel had become increasingly pious over the years. A few historians have speculated that her shift was motivated by guilt generated by the fuzzy circumstances of her first marriage, which was very ugly and ended with her fleeing her mildly unstable husband. During the campaigns of the 1820s, when people started questioning if that marriage had ever ended legally -- remember, Reagan is the only president to have been officially divorced -- Rachel got a case of the vapors. The stress might have helped to kill her.

Jackson wrote the epitaph on her grave, which reads as follows:

"Here lie the remains of Mrs. Rachel Jackson, wife of President Jackson, who died December 22nd 1828, aged 61. Her face was fair, her person pleasing, her temper amiable, and her heart kind. She delighted in relieving the wants of her fellow-creatures,and cultivated that divine pleasure by the most liberal and unpretending methods. To the poor she was a benefactress; to the rich she was an example; to the wretched a comforter; to the prosperous an ornament. Her pity went hand in hand with her benevolence; and she thanked her Creator for being able to do good. A being so gentle and so virtuous, slander might wound but could not dishonor. Even death, when he tore her from the arms of her husband, could but transplant her to the bosom of her God."

As cartoony as Jackson was, I think he was also genuine. His passions often got the better of him, but they also drove him to remarkable things. You read an epitaph like that, and you really do believe that his greatest reward for living was the chance to be buried in the ground next to his wife. Romance!

And speaking of romance, the Hermitage was actually one of the first presidential sites I visited as a stand-up comedian. One of my first audition trips took me to Nashville, where I slept on the couch of a generous friend. Looking for something to do during the day, I figured the Hermitage was as good a thing as any. I didn't realize at the time that it would be the start of a 10-year journey through American history. I didn't take any notes on my first visit, and I never bothered to write it up. By the time I realized I had accidentally developed a hobby, the memories were too dull to do the place justice. You can go home again.